Way too many children in Romania have been the victims

of abandonment! Whether they spend their childhood in orphanages, family-like

care systems or whether they are in the care of an extended family, for all of

them, the word home does not exist, or it exists in a seriously distorted way.

According to official statistics, as we speak, the

parents of almost 76 thousand children work abroad. As of late, the Ombudsman, Renate Weber, has stated the number of such children was much greater, more

than 100 thousand, which is appalling, she said, given that, for various

reasons, a great many of those children are not officially registered as such or

nobody cares about them.

Of the dozens of abandoned children, nearly 4,000 are

in 140 placement centres or thereabouts. Why did they end up being there? Giving

us an answer to this question, here is the development manager of an NGO, Hope

and Homes for Children, Robert Ion.

Robert Ion:

In Romania, one in three children lives

below the poverty limit and it is because of poverty that most of the children

end up in placement centres, at the moment. They are the 4th, the 5th,

the 6th child in their family, in most of the cases hailing from

rural areas, for whom there is nothing left at home. Children end up in placement

centres for various other reasons! It may very well be because their parents

work abroad. It could be because a child was abandoned in a hospital unit. It

could also happen because a legal entity ruled that the child be removed from

an abusive environment. And yet, were we to look at the most common cause of

the children being institutionalised, that is, nonetheless, poverty ʺ.

Time has told us that the chance for children in

orphanages to become the adults society expects them to be and, which is more important,

accepts, that chance is very slim.

Robert Ion:

ʺWhat

comes in handiest for us to do is to have the earmarked budget so that we can

prevent the separation of the child from their family. In all Romanian governments

after the Revolution, no such budget has been earmarked whatsoever. It does

exist, for the placement centres to be functional, and becomes operational once the

child is removed from his family, which is unusual. We should have a budget earmarking

in order to prevent the separation of the child from the family, so that we can help

the underprivileged parents or the children coming from vulnerable socio-economic milieus

to stay with their parents. Once the rift occurs, we’re speaking about a

tragedy, for the child, but also for the family, it’s something we have decided to sort out by institutionalising the child, who is in no way to blame, as regards

such dynamics. The programs preventing the child from being separated from their

family are, for their vast majority, supported by non-profit organisations,

such as ours. Longer term, we should also consider, as a country, opting for no

longer allowing for institutionalisation to be recognised as a form of child

protection. We wouldn’t opt for allowing our own children to be included in a placement

centre, but we think that is all right in the case of other children, and that

shouldn’t happen. We should have more prevention services, we should have as

many as possible family-type care homes, an as wide as possible network of

professional maternal trained nurses so that we may help parents keep their

children at home.

To that end, ʺHope and Homes for Childrenʺ, for instance, has

taken action along three directions.

Robert Ion:

We’ve been doing personalised work,

for each and every child and every separate family, so that we can offer what that child

or that family need. In some cases, that translates into medical treatment, in

other cases we prevent school dropout from happening, sometimes what we do means providing footwear,

clothes, essential goods, which, for various reasons, do not exist in

that family. We’re working on the closing of placement centres (through memoranda

signed by the County Councils and the General Directorate for Child protection)

and on replacing them with what we have termed Alternative Care Methods,

family-type homes, professional maternal assistance. and, to cut a long story

short, we help children who are no longer included in the protection system

when they turn 18 or 26, respectively, to make their first steps into the self-supportive

life. For such children, we pay rents, for instance, because, even though they

are recognised as a vulnerable population and are entitled to having access to

social housing, in Romania, there are not enough social housing lodgings, while

the youngsters who get out of the placement centres cannot access them, and the

alternative for them, as soon as they’ve been released from the centre, is simply

roughing it. And later, and with them, we need to find the answer to the

question Do they need more schooling or what job best suits them? For us, child

protection is of utmost importance so that is the area we get involved in. Everyone

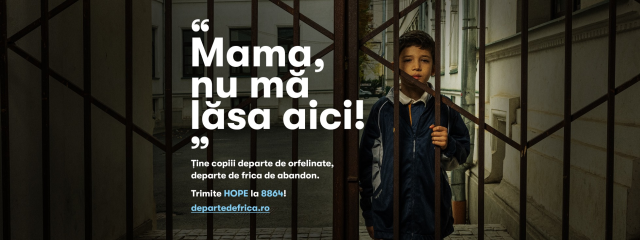

else can get involved, too, they can visit our website, at departedefrica.ro, if

they want to find out more about how exactly they can help the children we

support, or they can just text-message, hope, at 8864, for a monthly donation

of 4 Euros.

Among those who did get involved in that, albeit

differently, is Oana Dragulinescu. Oana is the founder of a Digital Museum of

Abandonment. The headquarters, a virtual one, actually, is the former hostel-hospital

for severely-disabled children in Sighetu Marmației, in the north. That hostel-hospital

is the strongest and most painful icon of abandonment and institutionalisation

in communist Romania before 1989. Closed down 20 years ago, the harrowing image of the hostel-hospital

in Sighet was preserved in most of the video recordings that

came to be known all over the world immediately after the revolution in

Romania. We want the Abandonment Museum to become a healing space of expression

for a community whose collective trauma has never been truly acknowledged and

discussed publicly. It is the trauma of the hundreds of thousands of children

who were abandoned during the communist years, but also during the country’s

recent history, or at least that is what Oana Dragulinescu says.

Oana Dragulinescu:

Whom should

the healing target? Probably us all, as a nation. I think we should heal ourselves of indifference, as

those institutions, we’re speaking about only one, that which was based in

Sighet, but there were several dozens of other institutions in that extreme

form, that of the hospital-hostels, such institutions were found in the city

centres, people like me and you used to

work there, and yet, in our interviews, it looks like nobody knew that, not

even the social assistance employees, they never imagined that something like that,

something appalling, happened in Sighet. I think it is something we resort to

whenever we see something horrendous, it is simpler for us to look the other

way. And that can really be simpler, short-term! Yet longer-term, here is

what happened when we looked the other way. In Romania, the abandonment rate did

not drop after 1989 and after Decree 770 was repealed, which banned abortion or

any form of contraception. And then, we may find it healing, to talk about that

aspect, I mean, to be able to realise that leaving the country to work abroad

for our children, so they can have a better life, may also be a form of abandonment,

a much softer one, definitely, and, viewed from such a perspective, talking about that,

we wanted it to be an out-and-out healing undertaking.

Let us not forget: abandonment is the most distressing form

of neglecting a child.

(Translation by Eugen Nasta)