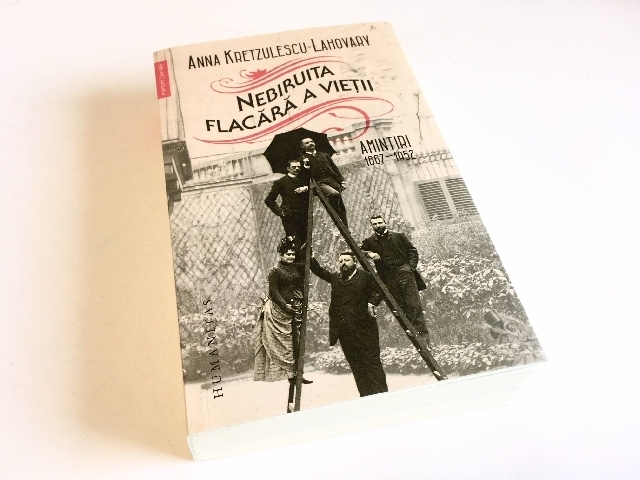

A part les grandes personnalités et événements cruciaux marquant l’histoire d’un pays, il y a les événements quotidiens et les acteurs anonymes, tout aussi importants. Parfois même, les faits apparemment insignifiants vécus par des personnes lambda finissent par définir une époque. Anna Kretzulescu-Lahovary a été une telle personne – discrète et jusqu’il y a peu, anonyme. Ses mémoires, publiés récemment aux éditions Humanitas sous le titre « La Flamme invincible de la vie », prouvent justement combien les gens ayant vécu à la fin du 19e et au début du 20e siècles ont été importants.

Descendante d’une famille ancienne de boyards – la famille Kretzulescu – elle est devenue, par son mariage, membre d’une autre famille, tout aussi illustre, celle de Lahovary. Anna est née en 1865 et elle a beaucoup voyagé, accompagnant son époux, le diplomate Alexandru Em. Lahovary, partout dans le monde. Le journal qu’elle a tenu pendant toute sa longue vie témoigne de l’amour de l’écriture d’une femme qui n’a pourtant pas eu de vocation littéraire, ainsi que de son amour pour les autres. Ses écrits évoquent des moments politiques et historiques importants, ainsi que des personnalités remarquables, tels le roi Carol Ier, la reine Elisabeta, la reine Marie, ainsi que d’autres hommes politiques, intellectuels et boyards importants de son époque.

Alina Pavelescu, celle qui a traduit en roumain les mémoires d’Anna Lahovary rédigées en français, raconte : «Anna Lahovary a vécu presqu’un siècle. Elle est décédée en fait quelques mois seulement avant son centième anniversaire. Elle a connu les années de la Première et la Seconde Guerre mondiale, traversant des moments dramatiques. Lors de la Première guerre mondiale, se trouvant à Paris, avec son époux, attaché de la délégation de la Roumanie dans la capitale française, elle a essayé d’introduire en Roumanie le modèle médical français et de l’adapter à la situation du pays. Elle a traversé une autre période difficile après la Première Guerre mondiale, quand les possessions de sa famille de la région d’Argeș ont été détruites par l’occupation allemande, de sorte qu’après 1920 elle est devenue simple fermière pour une certaine période, afin de sauver les biens de la famille. A suivi la fin douloureuse d’une époque de civilisation roumaine, suite à l’instauration du communisme, lorsque le monde construit par des familles comme celle d’Anna Lahovary s’est écroulé. Elle a pourtant gardé sa capacité à voir la beauté cachée des êtres et à ne pas désespérer devant la laideur, car celle-ci ne représente pas l’essence de l’humanité et du monde.»

Quoique bien élevée et respectant généralement l’étiquette du monde où elle vivait, Anna Kretzulescu-Lahovary se permettait de petites excentricités. Par exemple, après avoir déjà mis au monde plusieurs de ses 6 enfants – cinq filles et un garçon – elle a voulu colorer ses cheveux en rouge. Etant donné que cela aurait semblé bizarre dans les années 1890, quand la couleur naturelle des cheveux était à la mode, Anna a renoncé à cette idée, mais le fait d’y avoir pensé en dit long sur sa façon d’être – estime l’écrivaine Ioana Pârvulescu, qui nous donne d’autres détails sur l’époque, surpris par Anna Kretzulescu-Lahovary dans ses mémoires.

Ioana Pârvulescu : « En 1889, lorsque la Tour Eiffel a été inaugurée, quelqu’un qui revenait de Paris lui a apporté en souvenir une tour Eiffel en miniature, comme on en vend de nos jours. Je ne savais pas que ce genre d’objets-kitsch était mis en vente dès l’inauguration de la célèbre tour. Anna a fait un voyage en ballon, ce qui est aussi très intéressant. C’était en 1893 et elle a eu très peur, pourtant le voyage s’est bien passé. Elle décrit également les villes par lesquelles elle est passée, comme Saint-Pétersbourg, par exemple, ville où elle s’est mariée, à l’âge de 16 ans, ou Istanbul, qui, selon sa description, semblait sortie d’un roman d’aventures. Et elle a consacré, bien sûr, des pages très intéressantes à Bucarest. »

A compter de 1947, après l’instauration du communisme, Anna Kretzulescu-Lahovary et les membres de toutes les anciennes familles de boyards ont traversé des moments extrêmement difficiles : nationalisation, expropriation, pauvreté. Elle a tout supporté avec dignité, aux côtés de ses enfants et de ses petits-enfants. Sa dignité et sa résilience face aux difficultés étaient les conséquences de l’éducation qu’elle avait reçue et qu’elle a transmise, à son tour, à ses enfants et à ses descendants. Son arrière-petit-fils, l’architecte Şerban Sturdza, se rappelle avec beaucoup de fierté son arrière-grand-mère nonagénaire.

Ioana Pârvulescu : « Le dévouement envers les autres, l’envie de faire constamment quelque chose dans la famille ont été transmises d’une génération à l’autre et faisaient partie de la vie quotidienne. Il n’y avait pas de moments d’inactivité : on sculptait, on lisait, on tricotait un pull, on bricolait des porte-bonheur pour le 1er mars. Et toutes ces activités servaient à quelqu’un et à quelque chose. La féminité ou ce qu’être femme signifiait à l’époque ne coïncide pas avec ce que l’on pense de nos jours des femmes de ces temps-là. Ces femmes étaient capables, dotées d’humour et très actives, toujours occupées à faire quelque chose pour soutenir leur famille. »

Anna Kretzulescu-Lahovary a été, de ce point de vue aussi, une représentante de la féminité de la fin du 19e siècle, mais elle s’est également distinguée par des qualités personnelles que l’on peut découvrir en lisant ses mémoires. (Trad. : Dominique)