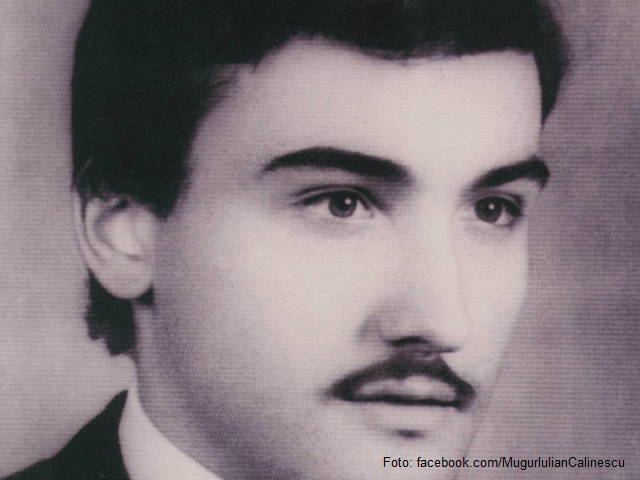

Mugur Călinescu’s name will forever remain in

the history of heroism as a man’s struggle with a cruel, much stronger enemy

but which did not frighten him. He is not only a Romanian hero, but also a

universal example for all the people who fight for the right cause of freedom

and dignity. Eventually, MugurCălinescu paid with his life for the

courage to think and act for justice and truth.

Mugur Călinescu was born on May 28, 1965 in

Botoșani, northeastern Romania. In 1981, at 16 years old, when he was an 11th grader

at the August Treboniu Laurian high school in his hometown, he

decided that his existence and that of those around him, in a country ruled by

a vicious communist regime, could not go on like that. So he decided to

protest. Călinescu’s moving story was told publicly in the early 1990s, in the

early years of freedom regained in December 1989, by the journalist, writer and

historian Constantin Iftime. Here he is at the microphone with details:

Constantin Iftime: He was a high school junior, going to Laurian

high school, but previously he had studied at Eminescu high school. He took the

math and physics exam, he was in a good class. His parents were separated, his

father was wealthy, he worked in a clothing manufacturing factory, he was the

chief tailor who made the patterns. He had a lot of money, he was a top tailor.

He bought his boy a Japanese radio recorder with which he tuned in to radio

Free Europe, and his mother did not know anything about that. He

was a clever boy, he listened to music, he read books, he had a curious nature.

On the night of September 12, 1981, Mugur left

the house determined to voice his discontent. He walked towards a metal fence

surrounding a building yard and wrote a slogan calling on people to oppose the

increasingly harsh living conditions. Today we find it unbelievable that

writing words on a wall is seen as an act of great courage. But it was an act

of courage during communism, when most people were terrorized and preferred to

keep silent. Constantin Iftime is back at the microphone with more:

Constantin Iftime: You may wonder where he got the idea from? It

was his own idea. He had some chalk at home, the type of chalk used by

foresters, which did not come off easily. And he started writing slogans, he

wrote the first slogans on some metal boards surrounding building yards. These

slogans referred to the people’s precarious material situation. His mother was

a saleswoman at the central store and had a small salary. It seems that there

was a lot of talk about money in his family. His mother was constantly under

pressure, they had cut about 30% of her salary, it was the period when the

authorities started cutting people’s salaries.

Another 31 nights followed, in which

Mugur Călinescu continued to write his discontent on the walls of the town’s

buildings. One of them was the headquarters of the county branch of the Romanian

Communist Party. He wrote on walls, on billboards, on road kerbs. The local branch

of the Securitate, the communist political police, went on maximum alert. Messages

would keep appearing, in places where the members of the political repression

structures least expected them, and they would be promptly erased. Where they

couldn’t be removed, the place would be painted over.

All the informants in all the

factories in the town were mobilised. In their desperate effort to capture the

author, the Securitate checked the records of all the apartment buildings, and

all the letters people would send to the party. More than 47,000 handwriting

samples were analysed, with the experts claiming that the author was a scholar or

a misfit. Night patrols and watches were organised. Until finally, on the night

of 18th October 1981, a patrol noticed a young man with a piece of

chalk in his hand, writing something on a wall. Constantin Iftime told us what

happened next.

Constantin Iftime: He had no

reaction. He was arrested, and he admitted to everything from the very

beginning. His mother knew nothing about him, she panicked and started calling

everywhere. She was only announced about the arrest the next day. He spent that

night being interrogated. He was taken straight to the Securitate offices,

because they were interested in who was behind this. They didn’t beat him up,

ironically it was his own father who threatened him, not the Securitate. The ones

who interrogated him were people who knew what was going on among students, and

they wanted to make him talk without resorting to violence. But they did put a

blinding light in his face and the Securitate guy was sitting behind that light.

Those hours spent with a light in his face must have made him hot, he already

had a fever, he had early-stage leukaemia. I think it was a period of hormonal imbalance

caused by severe stress. But my opinion is that he was killed by the

Securitate. He was a sensitive person, thrown into this extremely vicious

circle. He was a hardworking boy, a nice teenager, but everyone treated him

like an object.

His teachers reprimanded him, his father

attacked him for jeopardising his career, his mother suffered a trauma. Abandoned

by his family, isolated from his friends and colleagues, marginalised together

with his mother, Mugur Călinescu died of leukaemia on 14th February 1985,

at the age of 19.

He was awarded the title of fighter

against the totalitarian regime, post-mortem. A theatre play and a film, both

titled Uppercase Print, as well as a novel, are now keeping his memory alive. (tr. L. Simion, A.M. Popescu)