The archetype of the

intellectual politician in European history dates back to Roman antiquity, the

first example being Emperor Marcus Aurelius during the second century AD. In

his famous book about the ideal form of government, The Prince, Niccolo

Machiavelli writes that an intellectual prince will always find the right

solutions for political leadership. One example of intellectual prince in

Romanian history is the ruler of Wallachia, Neagoe Basarab, from the beginning

of the 16th century. However, the most famous was the Ruler of

Moldavia, Dimitrie Cantemir, who authored a vast number of books in different

fields, such as history, geography, morality, political science and music.

Dimitrie Cantemir was

born in 1673 as the son of Moldavian ruler Constantin Cantemir and was schooled

in the manner befitting the son of a ruler of the day. He was educated in the

capital of the Ottoman Empire, living and studying on the banks of the

Bosphorus between the age of 14 and 37. His works include the classic texts The

Divan or the Sage’s Dispute with the World, A Description of Moldavia, The

Hieroglific History and The History of the Growth and Decay of the Othman

Empire. Other equally important books are The Chronicle of the Romanian-Moldavian-Vlachs,

The Oriental Collection, Little Compendium on All Lesson of Logic, A Study

into the Nature of Monarchy, The Life of Constantin Cantemir known as The

Old, the Ruler of Moldavia, System of Muhammad Religion and The Book of the

Science of Music. In recognition of his extraordinary contributions to human

knowledge, in 1714, aged 41, Cantemir was elected as a member of the Royal Prussian

Academy of Sciences in Berlin. He was mentioned by the famous English historian

Edward Gibbon (1737-1794) in his book The History of the Decline and Fall of

the Roman Empire, as well as by the American historian of science Alan G.

Debus in a book about the 16th-century Flemish chemist Jan Baptist van Helmont.

As a political

leader, the career of Dimitrie Cantemir was not as impressive as that of him as

a scholar. He became the ruler of Moldavia in 1693, at the age of 20, after the

death of his father. 17 years later, in 1710, he became ruler for the second

time, but only for one year. He joined Peter the Great in the Russian-Turkish

war, but the Russians’ defeat at Stănileşti, in 1711, led to his losing the

throne. He went into exile at the court of Peter the Great, where he served as

his advisor. Cantemir died in 1723, aged 50.

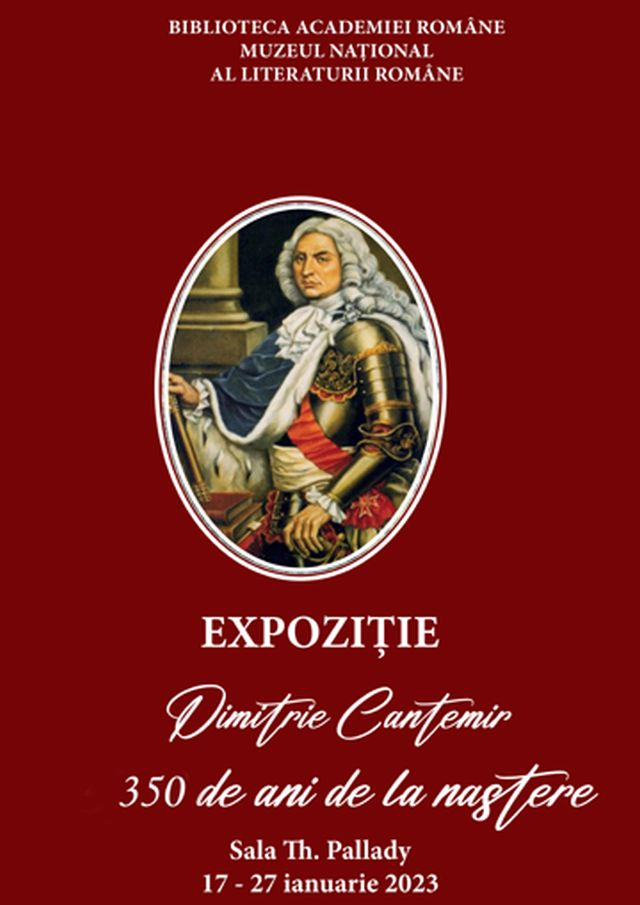

2023 was declared the

Year of Cantemir in Romania because it’s the 350th anniversary of his death and the 300th

anniversary of his birth. To mark this, the Romanian Academy Library opened an

exhibition of manuscripts and books dedicated to Cantemir. Academy member Răzvan

Theodorescu spoke about how Cantemir was a European figure typical of his day,

who brought together two cultural worlds, the West and the East.

Track: A lot is known about Cantemir, but many

other things are yet to be discovered. I remember that a few years ago at Belgium’s

National Academy in Brussels, a conference was organised on Cantemir’s European

identity. In this case, we gave the world a great European. We should never

forget that A Description of Moldavia was commissioned by the Academy in Berlin,

which at the time was commissioning various descriptions of Eastern territories.

This interest in the Levant, particularly in Prussia, was quite notable, hence

the work commissioned to Cantemir. In spite of the current political

circumstances, we should not shy away from saying that Dimitrie Cantemir became

a member of the Berlin Academy in his capacity as a Russian prince. When the

Prussian royalty thought of giving Peter the Great an accolade, and they chose

the most educated man in the Russian Empire, it was Cantemir, the former ruler

of Moldavia, that they suggested. Cantemir brought together the traditional

culture of this region, the Ottoman culture and the Russian one. In this

respect, he was a forerunner of the European identity, at a time when a new

Europe, the pre-modern Europe, was taking shape.

Constantin Barbu, an editor

of Dimitrie Cantemir’s works, discussed the manuscripts included in the

exhibition dedicated to the scholar:

Constantin Barbu:Around 200 volumes have survived of Cantemir’s

works, and so far we have printed 104 of them. I managed to compile two

manuscripts by Cantemir, they are now complete Cantemir works, and they can be

found in Moscow and here in Bucharest. We also brought several previously

unknown manuscripts by Cantemir. We also have, among others, two chapters from

A Description of Moldavia handwritten by the German Sinologist Gottlieb Siegfried Bayer, a professor at the

University of Petersburg. But Cantemir’s manuscripts are not only to be

found in Russia, but also at the Academy in Berlin, and we brought here the 15

manuscripts that they have.

The Year of Cantemir brings back to the

forefront an outstanding cultural personality, and, just as much, a remarkable

European. (CM, AMP)