Besides the big national sites involving gigantic projects, there were also smaller ones where factories were being built as well as blocks of flats, motorways and railroads. Romanias national construction sites were those for infrastructure such as hydropower plants, railroads, waterways like the Danube-Black Sea Canal, the Transfagarasan motorway that is crossing the Carpathians, the Peoples House (which later was turned into the Palace of Parliament) and the modern centre of the capital city, Bucharest.

Construction sites in communism were meant as a proof that the regime was still active making fresh jobs and houses for the people and that the communist leaders were the only ones able to bring joy to the people. However, the communist construction sites had a dark side, where inmates, sometimes political dissidents, as well as army troops were used as workforce. Improper safety standards leading to a large number of occupational accidents, as well as the tight control exerted by the then political police, the Securitate, made these construction sites look more like concentration camps. Add to it the lack of economic performance and loss incurred through waste, mismanagement and theft and youll get a clear picture of what a communist construction site looked like.

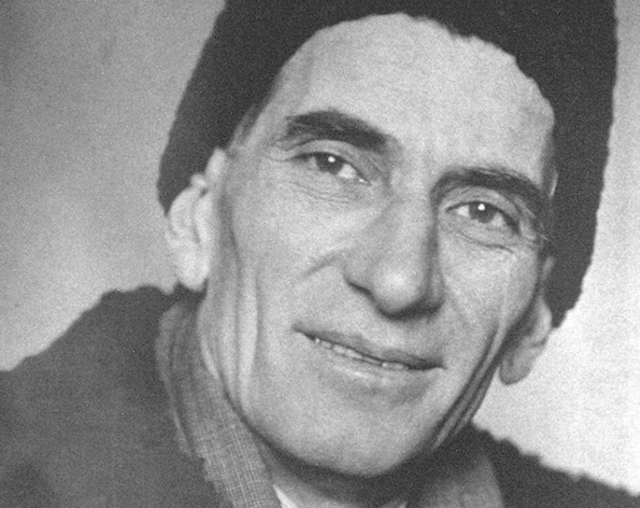

Historian Dinu Giurescu used to work for Sovromconstructia, a communist enterprise specialized in building motorways. He was dispatched to the site after having attended courses in road-building techniques by specialized engineers as well as classes of political economy and Marxism. In an interview he gave to Radio Romania in 2002, he explained how he ended up doing a different job than what he had initially chosen.

Dinu Giurescu: “I was a technician and had to calculate the efficiency and pays for various teams of workers. I was what they called at that time a tallier, and was doing the job while in my third and fourth years at the faculty. Back in the 1948-1949 period I wanted to become a teacher. I figured out that things were going in a certain direction at that time and I didnt have, what they called a good, ‘sound file. I graduated from the faculty in 1949 and remember I wasnt allowed to take my graduation exam.

The young intellectual Giurescu was forced to join a different social class of people, the working class: “People generally gave me a warm welcome when I joined their team and I am not speaking here about the other blue collars like me. However, I soon realized it was a jungle out there, joined by all the social-political losers. They were former army officers, lawyers, magistrates and accountants who wanted to get a safer job. There were all sorts of people on that site, some young and some old and I particularly remember a nice young guy, Dumitrescu, former officer in the Royal Guard. The sites chief engineer and the other chiefs we had were very interested in our activity and used to tell me: ‘make sure the workers are happy with their salaries and all. We dont want them to give up their jobs. We also had workers coming from the villages nearby.

Dinu Giurgescu has also worked on the building site of the aerodrome in Bacau, a secret military facility. He remembers that the site was under special supervision: “The site was closely monitored because it was a military facility. During the summer, army builders were brought in to work alongside us. The General Labour Directorate employees, who were not deemed worthy of wearing the uniform and defend the country, were incorporated into the directorates battalions. They wore blue-purple or blue-grey uniforms. They were simply used to provide manual labour. They would spend the whole duration of their military service, which lasted for two or three years, doing manual labour, and had their own supervisors. However, when they were sent to our site, they didnt have a supervisor, so I had to take over this task. I was on good terms with the warrant officer and I would sometime turn a blind eye to help them do their quotas.

One of the events no one who was around in the 1950s would ever forget was the death of Stalin. Dinu Giurgescu remembers he was at the building site when he learnt the news of Stalins death: “We were summoned to the canteen, which also served as a meeting hall, and someone informed us, in a very grave tone, of the death of the ‘greatest genius mankind had ever known, that is comrade Iosif Vissarionovici Stalin. They read out from an article in the newspaper Scanteia on this subject. Two or three people took the floor. We all knew what happened and behaved accordingly. My colleague Grigore Ioan told me privately afterwards: ‘The butcher is dead, I wonder what comes next. Three or four days after Stalins death I went to Bucharest for a few days and met one of the supervisors, Anton he was called, at the train station, and he told me: ‘Do you know Clement Gotwald of Czechoslovakia has also died?. And we smiled at each other, saying: ‘Maybe others will die, too. Thats what we were thinking, but our leaders didnt die.

The communist building policy came to an end in 1989. Although some say today it was not all bad, it had a mainly repressive purpose, which far outdid its basic function.