The history of the mass media during communist years includes a small, somewhat honourable chapter, in which journalists tried to implement professional ethics and be the voice of society. The years between 1966 and 1971 were the best for the media under the communist regime, and some shows were successful with the public. This was the case of the “Reflector” television show in which dysfunctions in public institutions and abuse by political actors were exposed to public judgment.

“Reflector” was an attempt at trustworthy journalism, although within certain limits. The ideology of the Romanian Communist Party was off limits, and so were the nature of the government’s power, the social and political order. Equally taboo were the leader Nicolae Ceaușescu, his family and relatives, senior party officials, the army, the repressive apparatus formed by the Militia and the Securitate, the judiciary and the financial-banking sector. As a rule, “Reflector” addressed abuse and irregularities in the consumer economy sector.

“Reflector” started in 1967 and was designed after similar shows in the Western press. The opening of the Romanian Television to the West was due to the journalists Silviu Brucan, the president of the public television broadcaster, influenced by the US media, and Tudor Vornicu, a former correspondent in France and familiar with the French media.

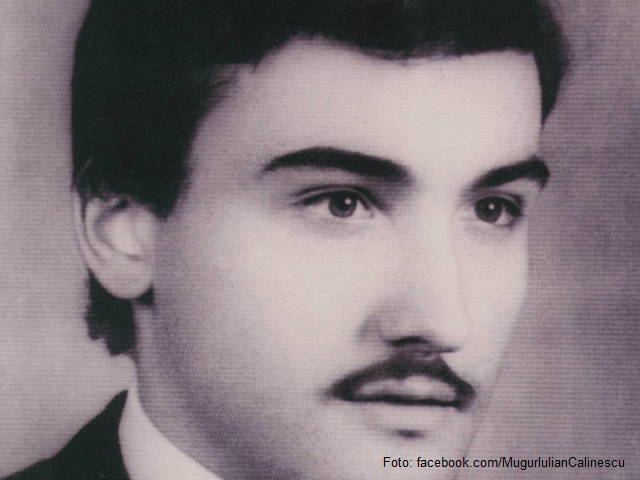

The journalist Ion Bucheru, then vice-president of the Romanian Television, was the one who coordinated the show’s production team. In a 1997 interview for the Oral History Centre of the Romanian Radio Broadcasting Corporation, Bucheru explained what the success of the segment actually meant:

Ion Bucheru: “I was in charge of ‘Reflector’ on behalf of the institution’s management. During those years, Reflector had come to be aired twice a week, while another show, ‘Ancheta sociala’ (‘Social Inquiry’), was broadcast at least every two weeks. ‘Reflector’ was 20-25 minute long, and ‘Ancheta’ had reached 50 minutes and even an hour, it had become an institution. People would write to ‘Reflector’ and to ‘Ancheta sociala’. The 5 people who were producing the ‘Reflector’ were like prosecutors who exercised their profession on behalf of the people. They had personal correspondence, they were simply called by people who no longer had any other hope or by institutions that had exhausted all legal means of settling disputes with private individuals or with other institutions.”

Appearing on television in those days, especially in outrageous cases of abuse, incompetence or negligent handling of public property, was something of an ominous prospect for anyone. That is why the name ‘Reflector’ sparked panic whenever it was pronounced.

Ion Bucheru: “We had reached a point where we were ending the ‘Reflector’ segment with a frame, an image and a text. The image showed a black car driving away in exhaust smoke or dust, and the text would read, ‘In this car, comrade minister so-and-so is leaving the ministry, probably summoned in a hurry to a party meeting, so hurried that he didn’t have time to talk to the ‘Reflector’ reporter who asked for his opinion on this issue that you’ve just seen and which is happening within the scope of his responsibilities’. This was frequently said on air. Well, when a company manager or a deputy minister heard about or got news on the phone that ‘Reflector’ had arrived on the premises or that someone from ‘Reflector’ had called to say that they would come in tomorrow or the day after to shoot, you can’t imagine the commotion that would create!”

July 1971, with the announcement of the infamous “Theses” by Nicolae Ceaușescu himself, under the official name “Proposed measures for the improvement of political-ideological activity, of the Marxist–Leninist education of Party members, of all working people,” meant a U-turn from the regime’s previous openness. It was a return to the harshness of the Stalinist years, a great surprise for the Western countries that had appreciated the Romanian leader’s position up to then.

That return also impacted the “Reflector”, which gradually lost its incisiveness and appeal.

Ion Bucheru: “The July Theses sprang from Ceaușescu’s mind, head and pen following a scandal caused by the television. After 1968, Ceaușescu had reached the peak of his popularity, of domestic and international prestige. It was a time when Romania was viewed internationally as some kind of miracle in this corner of Europe. It was a time when foreign heads of state opened their doors, gates, even the most conservative ones, even those who had previously rejected any thought of welcoming Ceauşescu or conferring him the honours worthy of head of state. It was a time when if you said you were a Romanian journalist abroad, and I experienced this firsthand and I can say this with full knowledge of the facts, you were received not with sympathy but with a kind of brotherhood. We would go abroad without equipment, without money, without logistical means, because we were poor, poorly equipped and really underpaid. But there was such a wave of sympathy around us that we were given so much of what we didn’t have and they had in abundance.”

Eventually shut down in the mid-1980s, when the entire television broadcast had been cut to two hours a day, ‘Reflector’ was re-established after 1989. But in the new era of freedom, it never reached the same level of popularity. (AMP)