The Old Orhei, Orheiul Vechi, in Romanian, is a museum compound on the valley of river Raut, a right-hand side tributary of river Dniester, in Republic of Moldova. The Old Orhei cultural-natural reserve enjoys a special status and is Republic of Moldova’s most important site. Currently a process is ongoing, for the Old Orhei to be included on UNESCO’s World heritage List.

The compound is made of several dozens of hectares of Orhei medieval town. Orhei is a settlement of the 13th and the 16th centuries. It is known as Old Orhei. We recall initially the settlement was deserted and a new city was established in a different location, bearing the same name, today’s Orhei, a town in Republic of Moldova’s Orhei district.

Part of the compound are two large promontories, Pestere and Butuceni. Added to them are three smaller adjoining promontories, Potarca, Selitra and Scoc. On the territory of the promontories the ruins of several fortifications can be found, as well as dwelling places, baths, worship sites, that including cave monasteries, dating from the Tartar-Mongolian period, the 13th to 14th centuries, but also from the Moldavian period, 14th to 16th centuries.

The Old Orhei Compound is a system made of cultural and nature elements, such as a natural archaic landscape, biodiversity, an exceptional archaeological environment, historical-architectural diversity, a rural traditional habitat and ethnographic originality.

The medieval settlement of Old Orhei saw its heyday several times. During the 12th to the 14th centuries, the period before the Tartar-Mongolian invasion. In the early days of the medieval settlement, the wooden and earth citadel is believed to have been erected in that period of time. The Golden Horde Age of the 14th century, the period the stone fortress dates from. Between the 14th and the 16th centuries, the settlement was included in the Moldavian state, for the town, it was a period of transformation, from an Oriental settlement into a Moldavian town.

During Stephen the Great’s reign (1438-1504) the stone fortress was repaired, and strengthened. In the 60s of the 15th century, the Orhei citadel was erected. It was a defense centre of the country’s eastern borders against the Tartar invasions. The Tartar invasions in the summer of 1469 prompted Stephen the Great to take measures, in a bid to strengthen the country’s defence capacity along Dniester River, initiating important works, carried in order to build a strengthened citadel in Orhei.

The archaeological excavations that made possible the discovery of the citadel’s foundation speak about those events. Similarly, the official documents of that time speak about that as well. So, in Stephen the Great’s charter of April 1st, 1470, for the first time the mention is made of a burgrave, that is a military commander of the Orhei citadel. We recall at that time the burgrave had military but also administrative responsibilities of the Orhei district.

The period of decay begins in mid-16th century and lasts until the early 17th century, when the inhabitants abandon the Old Orhei, moving into the new settlement, today’s Orhei. The stone citadel is destroyed.

Stefan Chelban is the Reserve’s Head of Archelogy and Ethnography Service. We sat down and talked to Stefan Chelban about the history of the Old Orhei:

„The Old Orhei is a nature cultural reserve set up in 1968, yet, in time, it has been going through several restructuring and reorganizing processes. The reserve is made of several localities and its purpose is to preserve the region’s natural heritage, but also its cultural heritage.

Actually, it was one of the main reasons why the reserve was set up. Arguably, it is one of the areas with the biggest number of assets part of the archaeological and ethnographic heritage, but also of assets of the immaterial heritage and such like. So, it is a region where the cultural heritage has been acceptably well preserved, to this day. “

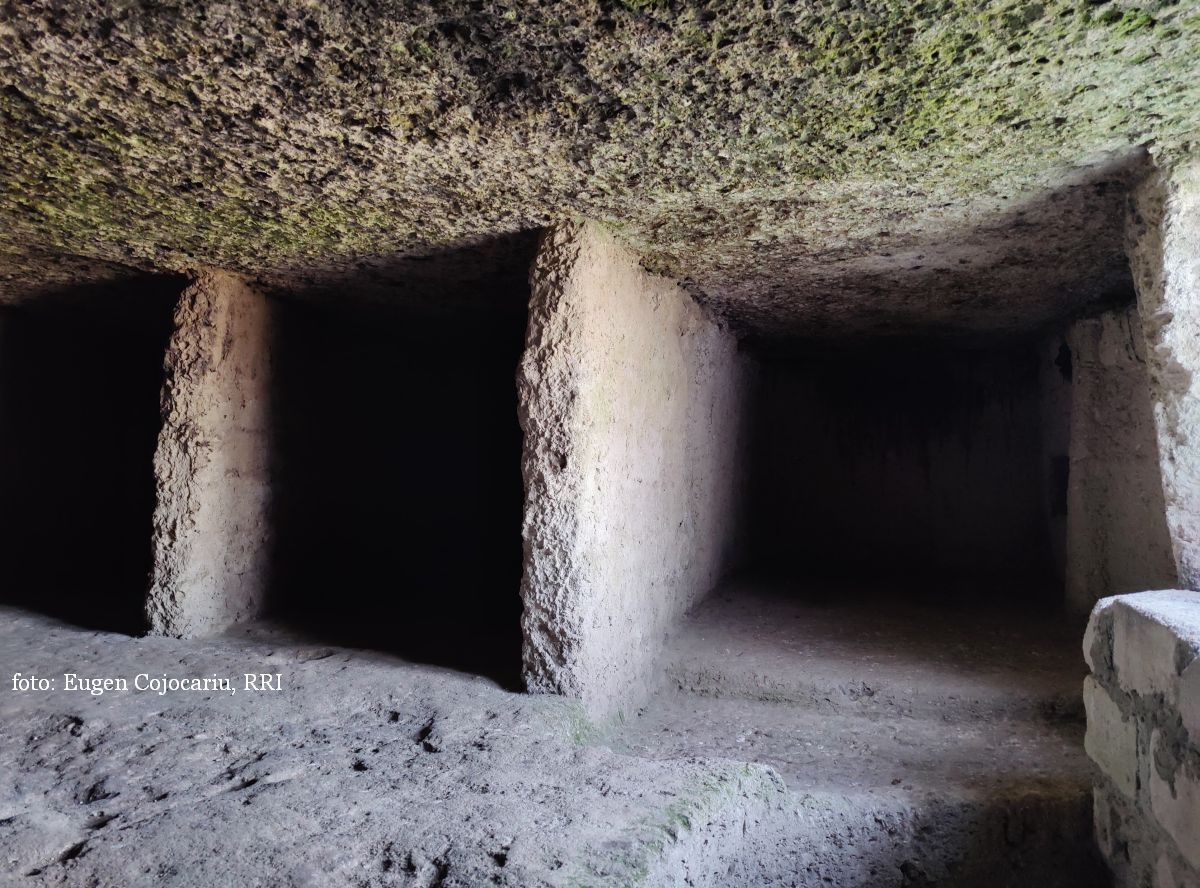

The Old Orhei’s cave monasteries are part of a cave remains compound. They are located in the lime rocks on the Raut River valley. The compound is extremely attractive in terms of tourism; it includes roughly 350 cave remains, of which around 100 are man-dug rooms, while the remaining 200 are karstic formations, grouped in six compounds. They include well-defined monasteries, underground churches, galleries and cells.

Here is Stefan Chelban once again, this time speaking about the cave monasteries and about the reserve:

Track: ”This is likely to be the central point for many, yet the reserve has a lot more to offer. For instance, the ruins of the Tartar city, a city that used to be here in the 14th century, albeit for a short period of time yet worth visiting all the same, that including the ruins of an old mosque which, judging by its surface area, it was allegedly South-east Europe’s biggest mosque.

Ștefan Chelban also told us something about the Old Orhei museum compound:

“The Ethnography Museum is a model of traditional architecture, specific for the late 19th century and the late 20th century. This house has been restored, refurbished with EU funds, using only traditional material and techniques.”

Here is Ștefan Chelban once again, giving us further details on the monastic life of the Cave monastery in the Old Orhei:

„We understand initially the monastery was inhabited by 12 monks since there are 12 cells by means of which we can tell each cell was individual, so there were 12 monks. We do not know exactly the year when it was built, yet that happened somewhere between 14th to 15th centuries. ”