One of Bucharests interesting museums lies in the northern part of the city, which is actually a residential area where the development of property and the increasingly urbanized character saw their heyday in the inter-war period. The Krikor H. Zambaccian museum is venued by purpose-built premises, capable of hosting a fine art collection. The museum is the brainchild of a merchant with a special personality. He was an art aficionado, also willing to give artists a hand. Born in 1889 in Constanta, in the south-east, Krikor Zambaccian hailed from an Armenian family. He continued the merchant tradition of the family, first in his native city then in Bucharest, where he relocated in 1923. However, fins arts remined his passion throughout. Museographer with the Art Collections Museum, Ilinca Damian, provided the details.

Ilinca Damian:

“The family moved to Bucharest, also developing their trade in Romanias capital city. All his life Zambaccian was in the fabric printing business and in the textile material trade, in a broader sense. Apart from that, his great passion was collecting fine art objects, in principal Romanian paintings and in the subsidiary, French paintings. Zambaccian discovered his passion for art when he was a student in Paris. In between accounting and economics courses he found the time to visit art galleries and museums, also taking part in conferences and debates. That is how Zambaccian became a self-made man in the field of fine arts. He succeeded to befriend some of the French artists, such as Henri Matisse. When he returned to Romania, he also befriended the Romanian artists of his generation. Gradually, Krikor Zambaccian began to structure his collection.”

That occurred properly after he relocated to Bucharest, in 1923. We recall that the items he had purchased before that year, in his first attempt to start a collection, got lost during World War One. The first fine art works he purchased as a collector were authored by the artists he had already befriended.

Ilinca Damian:

“All his life he maintained a close friendship with painter Gh. Petrascu. Every so often he would buy works created by the maestro, whom he visited on Sundays, he also had a close friendship with Th. Pallady, who visited Zambaccian in his study. Also, he was a friend of Nicolae Tonitza, temporarily, he was also a friend of Francisc Sirato. Actually, he was a friend of almost all the artists of the time, supporting them all his life to the best of his abilities. So, apart from his fine art collector activity, he also was a Maecenas of fine artists..Just like any other art collector of the time, Zambaccian knew how to add to his collection works by the so-called “forefathers of Romanian modern art”, the likes of Nicolae Grigorescu, Ion Andreescu, Ștefan Luchian, as well as Theodor Aman. The selection of Luchians paintings he purchased was acclaimed from the very beginning. Zambaccian himself did not mince his words saying he dedicated Stefan Luchian an altar, in his collection. Also, he was generous enough to pay good money for the paintings he purchased directly from the artists themselves of from other collectors. He believed a work of quality deserved being purchased for a good price, so he would always offer more money rather than start a negotiation.

In time, Zambaccians collection was growing, so he needed proper premises for the storage and display of the paintings. In the early 1940s, Krikor Zambaccian had a house built, which had been thought out as a museum but also as lodgings. It is the building of the Zambaccian museum we can still see today.

Ilinca Damian:

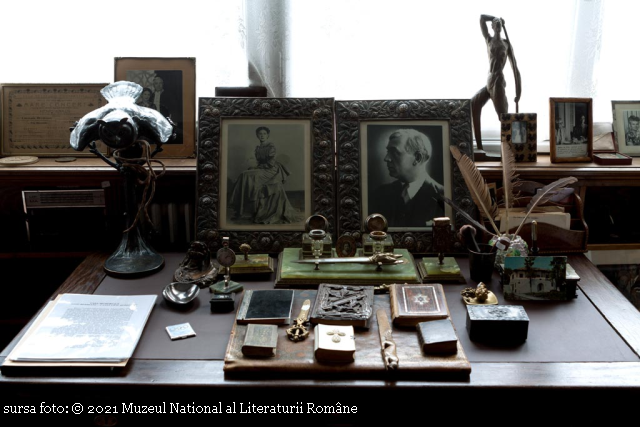

“In 1942, works for the building had already been completed, and visiting was allowed once a week. Zambaccian had though it out it out as a museum, but he obviously lived there until the year of his death, 1962. The house was designed in the modernist style. Actually, it was a medley of styles, from the neo-Romanian to the minimalist one, also having Moorish influences. So we can say the house had rather an eclectic style, but the main trend was the modernist one quite all right. The idea of opening a museum occurred to Zambaccian as early as 1932-1933. Even before he had the house built he initiated talks with the municipality of Bucharest, but they failed to reach an agreement as to the premises where the works of art would be exhibited. The initial plan was to donate the art collection stored in the house he lived in at that time, which was obviously inappropriate for exhibiting and visiting purposes. Negotiations with the municipality had no positive outcome, yet Zambaccian was adamant in fulfilling his wish, that of creating an open-to-everybody museum. So the 1940s he had his own house built, which clearly had that purpose, and in 1947 he succeeded to donate his Romanian art collection to the state. The donation proper was completed in three stages, in 1947, 1957 and 1962, the year of his death. As we speak, the collection includes 300 works of Romanian and European painting and sculpture.”

During the communist regime, the collection was unfortunately taken to other premises, it was a museum of several art collections, while Zambaccians house was used for purposes that were different from what the collectors initial intended. In the early 2000, in the wake of a large-scale restoration process, the collection was returned to its original building. Today, the Zambaccian residence but also the collection are open to visitors, just as their creator and initial owner wanted.

(Translation by Eugen Nasta)