The way in which society manages the issue of abandoned children is indicative of the civilization standard which the respective society has reached. In the past centuries, abandonment was a current issue. Modern society has come up with institutional solutions to that problem, but institutionalization is not sufficient in itself.

More details from philosopher Gabriel Liiceanu: The fact that abandoned children can be given in foster care is the progress of world civilization. Regarded from outside that is obviously a step forward, it means progress. Progress as compared to what? In the late 18th century, one of the European men of culture, an idol of Western spirituality, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, regarded as one of the world’s great pedagogues, wrote solid treatises on the way children should be educated, but on the other hand, he would abandon his own children on the church stairs. That was the way in which society at that time would deal with the impossibility of looking after unwanted children.

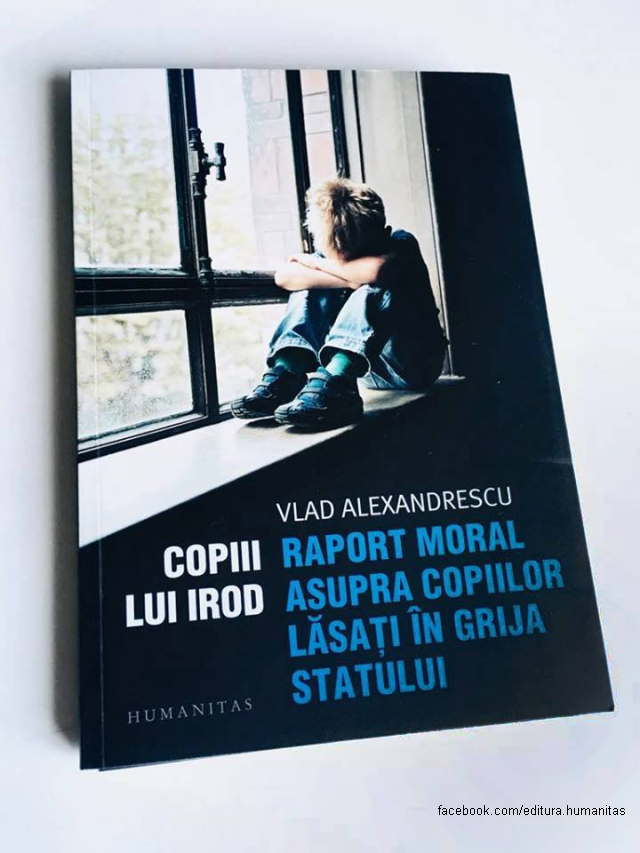

Humanitas Publishers hosted the launch of a book including the report on institutionalized children in Romania, entitled Herod’s Children. The author of the report, MP Vlad Alexandrescu paid several fact-finding visits asking for details about those children’s health condition: I took action in my capacity as an MP, namely parliamentary interpellations and very precise questions to relevant institutions, as regards the number of abused children, the kind of abuses registered by the police, medical treatments, psychiatric treatments which children undergo, the type of psychiatric medication they get. I also asked questions about human trafficking practiced abroad, children or young people being many of such victims. The outcome of those undertakings is this report, generously released for the first time as a book by Humanitas Publishers.

Dire poverty seems to be the main cause of the abandonment of new-born or little children. The traumatic experience those unwanted children have has deep follow-ups affecting their normal psychic and emotional development.

Vlad Alexandrescu: That is the case of about 65% of children given in state care. They come from families living in dire poverty. Institutionalization is one of the effects of dire poverty in Romania. Many of those children are abandoned when they were born or shortly after they have been born. Some of them stay in hospitals before being given in state care. A hospital is not a place where a child could grow up. That is why, when they are already a few months old, they suffer from abandonment trauma, which little by little, turns into psychic suffering.

The communist period disrupted the social balance producing a generation of unwanted children, dubbed the decree generation. Under Decree of October 1st 1966, Nicolae Ceausescu banned abortions with a few exceptions. In 1990 the New York Times carried an article on abandoned children in the communist years because of Ceausescu’s legislation banning even contraception methods. Shortly after the 1989 revolution, orphanages in Romania were full of unwanted children, most of them suffering from serious psychic disorders. Although today’s laws no longer allow for such dramas, some abandoned children continue to be patients of psychiatric wards.

Vlad Alexandrescu: There is a prejudice in Romanian psychiatry. Somehow, that makes psychiatrists expect an institutionalized child to come to hospital as something normal. Of course, after a child’s admission to a psychiatric ward and the use of neuroleptic medicines, the psychiatrist recommends the child’s periodical reevaluation and the gradual introduction of psychic therapy. However, such a therapy is never used.

Gabriel Liiceanu believes that the shortage of funds and bureaucracy are not the only causes of the low investment in foster homes, which is in tune with the times society is going through. Despite the controls conducted, the warnings of TV broadcasters and investigation articles, the fight with that giant-institution might seem lost. However, solidarity and the involvement of society as a whole might comfort the suffering of abandoned children.

Gabriel Liiceanu: On the other hand, the author of the book says that if we got all the money in the world to invest in foster homes, the problem would not be solved because it is engulfed in a terrible bureaucracy, which can no longer be dismantled. What can each of us do after realizing that? We can do nothing all by ourselves. You cry, food gets stuck in your throat, you go to bed with gloomy thoughts about mankind. But together we can succeed. Solutions can be found as a result of those experiences because indignation is the centerpiece of a society’s life. You live as long as you are outraged. Does nothing stir your indignation? You are a dead man and the world around you goes under.

Vlad Alexandrescu’s book Herod’s Children. Moral Report on Children Left in State Care will also be accompanied by an e-Book launched by Humanitas Publishers. (translation by AM Palcu)