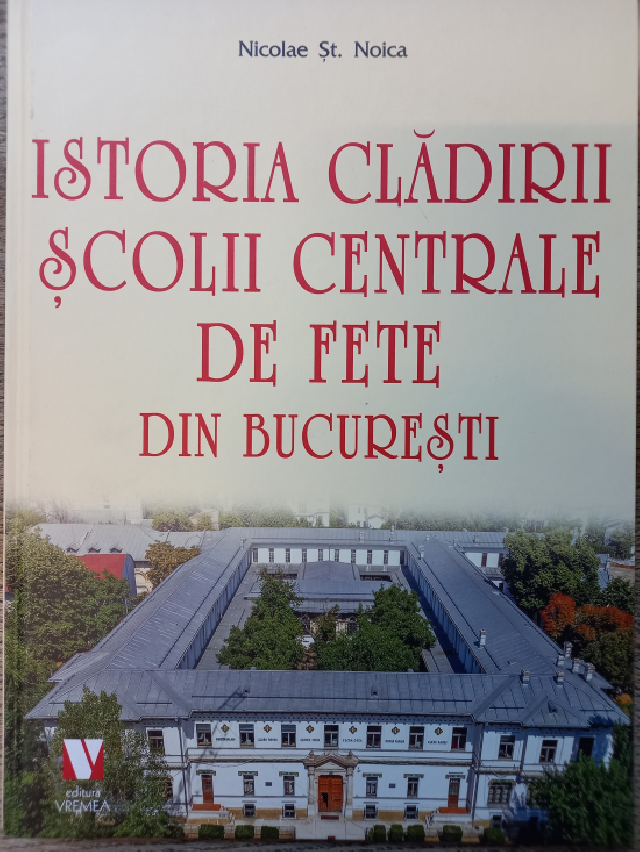

L’École Centrale de jeunes filles

occupe une place à part parmi les anciens lycées de Bucarest, aussi bien par

l’instruction de haut niveau traditionnellement dispensée par son corps

enseignant que par le bâtiment où elle fonctionne. Une construction

représentative du style architectural appelé « national » ou

« néo-roumain », qui commençait à se répandre. Imaginé par

l’architecte Ion Mincu, auteur du projet de l’École

Centrale, ce style a pris son envol grâce aux contributions ultérieures

d’autres architectes, pour atteindre son sommet à l’entre-deux-guerres, quand

il est devenu le style préféré pour la construction de bâtiments publics et

privés dans la Grande Roumanie de l’époque. Quels que soient, pourtant,

les changements intervenus au fil du temps, les lignes directrices du début

sont visibles dans le style architectural très particulier de l’École Centrale de jeunes filles

de Bucarest. Fondé en 1852, lors du règne du prince de Valachie, Barbu

Știerbey, l’établissement fonctionnait dans un bâtiment inadéquat durant

plusieurs années, après la proclamation du Royaume de Roumanie en 1881.

D’ailleurs,

immédiatement après cette date, le Parlement a adopté un ample programme de

construction de bâtiments publics, dont des établissements scolaires, en y

allouant des fonds importants, explique Nicolae Șt. Noica, auteur du livre « L’histoire

du bâtiment de l’École Centrale de

jeunes filles de Bucarest » C’est un projet de loi ciblé sur les établissements scolaires et

les institutions culturelles d’enseignement dont le fonds alloué est très

élevé, environ 10% du budget national de l’époque. (…) Entre 10% et 12% alloué

uniquement à la construction d’édifices. Le premier pas est fait en 1885. L’architecte

Ion Mincu signe un contrat pour réaliser le plan de l’École Centrale de jeunes filles. Le projet précisait

toutes les fonctions que le bâtiment devait remplir. La superficie et la

hauteur des salles de classe devaient assurer 7 mètres cubes d’air par élève. À

la bibliothèque, où les jeunes filles passaient plus de temps qu’en classe, le

volume d’air prévu était de 9 mètres cubes par élève. L’architecte Ion Mincu a

respecté ces exigences à la lettre, en projetant un bâtiment rectangulaire,

avec sous-sol, rez-de-chaussée et un étage. À l’époque, il y avait aussi un

internat et une cantine.

Après une modification du programme de

construction initial proposé par le ministère de l’Éducation et après la tenue

d’un appel d’offres pour choisir le constructeur et dont le gagnant a été

l’entreprise de l’ingénieur Sicard, le coup d’envoi des travaux fut donné en

1888. Deux années plus tard, en 1890, l’École Centrale de jeunes filles quittait son ancienne adresse,

près de l’hôpital Colțea, et emménageait dans son nouvel édifice, qui existe

toujours, en face du jardin public de Grădina Icoanei. L’architecte Ion Mincu a

adapté sa vision artistique de manière à assurer aux élèves le confort

nécessaire pour étudier, ajoute Nicolae Șt. Noica: Au centre du

bâtiment rectangulaire, il y avait une cour intérieure exceptionnellement belle

aujourd’hui encore, cent ans plus tard. Elle était conçue pour y passer les

moments de récréation. Il est intéressant à remarquer le fait que le corridor

qui donnait sur le jardin a été fermé avec des colonnes rappelant celles des

monastères. (…) Au départ, Mincu voulait le laisser ouvert, mais, vu le climat

local, il a décidé de le fermer, mais, à la différence des monastères, il y a

installé un système de fenêtres très bien réalisées, qui fonctionnent toujours.

Cela a marqué l’apparition d’un nouveau style architectural.

Ce nouveau style mettait ensemble l’architecture vernaculaire, le style

brancovan et l’architecture religieuse autochtone, en y ajoutant des ornements

empruntés à l’espace méditerranéen. La faïence colorée utilisée dans la zone

des corniches en est une preuve incontestable. Et c’est toujours dans cette

partie haute du bâtiment que sont inscrits les noms des plus illustres

princesses valaques, impliquées dans le soutien à la culture et à l’éducation. En

fouillant dans les archives pour retrouver les plans originaux dessinés par Ion

Mincu, Nicolae Șt.Noica a aussi découvert d’autres documents qui montrent

l’intérêt pour l’enseignement, manifesté par la société à cette époque de

refonte du pays: J’ai trouvé les fiches de paye des

enseignantes qui travaillaient dans cette école à l’époque. (…) Une prof de

géographie, d’histoire ou de roumain recevait 270 lei or. Un gramme d’or était

valait 3 lei, donc 270 divisés par 3 égal 90, donc 90 grammes d’or. Aujourd’hui,

le gramme d’or se vend et s’achète à 200 lei. 90 multipliés par 200 font

18.000. À l’heure actuelle, aucun président ou ministre n’a un salaire de

18.000. Alors, l’assertion au’il y avait peu d’argent à l’époque ne se vérifie

pas. Les artisans étaient respectés, tout comme les enseignants. Et les

résultats ont été visibles à travers le temps.

Aujourd’hui,

170 ans après la fondation de l’École

Centrale de jeunes filles et 132 après l’inauguration

de son siège actuel, le bâtiment imaginé par Ion Mincu peut être admiré dans

forme d’origine. (Trad. Ileana Ţăroi)