The Cotroceni Palace in Bucharest used to be a royal

residence. Today it is the main building of the Presidential Administration.

Right opposite to it, in the posh Cotroceni area, we can find two memorial

houses dedicated to two of Romania’s interwar writers. They were so different

from one another in terms of writing, yet they were so close in mundane life:

they were actually close friends. They are prose writer Liviu Rebreanu and poet

Ion Minulescu. In the former case, the museum-apartment bears the name of Liviu

Rebreanu and his wife, Fanny Rebreanu, with the apartment being the only one

such site in Bucharest where then the family’s domestic atmosphere has been

recomposed; so was the writer’s study with his bookcase and the writer’s

personal items. Liviu Rebreanu was a member of the Romanian Academy and a

dignitary holding quite a few official positions. A textbook prose writer,

Liviu Rebreanu was born in Transylvania, at a time when Transylvania was still

part of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. Among other things, Liviu Rebreanu is

remembered as the author who captured the psychology of his characters in an

utterly realistic manner. Rebreanu was born in 1885 and died in 1944, shortly

before the communist regime was instated in Romania. In 1934, he bought the

apartment in Cotroceni for his adoptive daughter, Puia-Florica Rebreanu. Liviu

Rebreanu never lived there, yet the house has emphatically preserved the daily

life of the family’s intimacy. Here is museographer Adrian David, with details

on that.

The residence has quite aptly earned

the status of Liviu Rebreanu Memorial House because, after the writer died in

Valea Mare, near Pitesti, his wife move to this apartment with her daughter and

son-in-law, and here they transferred whatever it was that they could retrieve from the writer’s former real estate property. The apartment, today known as the

Rebreanu Memorial House was donated to

the Museum of Romanian Literature in 1992 by the writer’s adoptive daughter,

Puia Rebreanu. When the former owner dies in 1995 and following a time when the

residence was refurbished, the apartment entered the museum circuit, in effect

belonging to the Romanian state, together

So those who, at present, may want to get the chance

to know Rebreanu in the intimacy of his family, can travel to the Cotroceni

area and visit the little block of flats where the museum-apartment can be

found.

Museographer Adrian David:

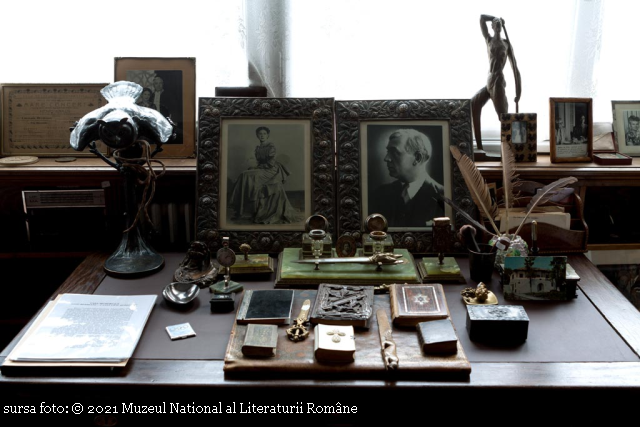

Rebreanu’s desk, where he sat down and

wrote his entire work…Those who come visit may notice, for instance, near the desk,

the oriental table for the writer’s coffee serving set, these two items were

always there since he was a coffee addict and a night-time writer. We’ve got

Rebreanu’s lamp, owl-shaped and which Rebreanu had on the desk all the time. We

have a clock Rebreanu brought for himself from his native Transylvania which

back then was under Austrian-Hungarian occupation, It was an imperial clock, which

took him back to the native region he had no choice other than leaving and

relocating to the Old Kingdom. But over and above anything else,

attention-grabbing for those who step into the memorial house is the lavish

display of fine art. There are a great many works, most of them authored by

some of Rebreanu’s friends, some of them were even made in Liviu Rebreanu’s

house. For instance, in the lobby there are three portraits drawn by Iosif

Iser. There were there after the 1913 Christmas, held in the Rebreanus’ house,

where among the guests were painters Camil Ressu, Iosif Iser, alongside other

very good friends. During that Christmas evening the fir-tree was on fire because

of the candles, and, according to Puia Rebreanu’s own account, all the presents

they received for Christmas were burned. But, she said, thank God Iosif Iser’s

drawings remained intact, bringing back the memories of that day. Also, there

are many icons, all of them from Transylvania. Rebreanu was very religious and

very superstitious.

In stark contrast with Liviu Rebreanu, another author

lived in the adjoining apartment. He was symbolist poet Ion Minulescu, who was

born in 1881 and who died also in 1944. His verse was extremely popular among

the sentimental youth of that time. Even the design of that home, which was a

lot more spacious, was different, as the imprint was that of a much more

bohemian atmosphere as against the restraint of the Rebreanu residence.

Adrian

David:

The block of flats where both memorial houses can be found, that of Ion

Minulescu and that of Liviu Rebreanu, was brought into service in 1934. Back in

the day it was known as the Professors’ Block of flats and was purpose-built

for the teaching staff. Ion Minulescu’s wife, poet Claudia Millian, was a

high-school teacher and a principal. Liviu Rebreanu got hold of the apartment

with the help of Ion Minulescu, who facilitated Rebreanu a loan from the

Teaching Staff Center. In the meantime, the two writers’ wives and daughters

became friends. Actually, in the Ion Minulescu Claudia Millian Memorial

House, all family members are represented in equal proportion, since, apart

from Ion Minulescu, with whom we are very familiar, his wife and daughter were

also artists and writers. Claudia graduated form the Conservatory of Dramatic

Art, while Mioara Minulescu, their daughter, initially read Letters and the

French language. Actually, Claudia Millian also studied with the Fine Arts

Academy in the country and in Paris, while Mioara Minulescu studied at the Fine

Arts Academy in Rome. And indeed, here, on the premises, there are a great many

works signed by the two: mosaics, paintings, sculptures and various works of

art.

Apart from the two landlords’ works of art, the

memorial house also plays host to the work of some friends of the family.

Adrian David:

With Minulescu, there are more than

100 paintings. There are a couple of dozen sculptures. All signed by great

names of the domestic fine arts, part of whom were very good friends of Claudia

Milian’s. Her best friends were Cecilia Cuțescu- Storck and her sister, Ortansa

Satmari.

In the mid-1990s, after the death of the two writers’

daughters, Puia Rebreanu and Mioara Minulescu, the two apartments were donated

to the state so that they could be turned into memorial houses highlighting the

activity of the two writers, but also the personality of the women who stood by

their side.