The

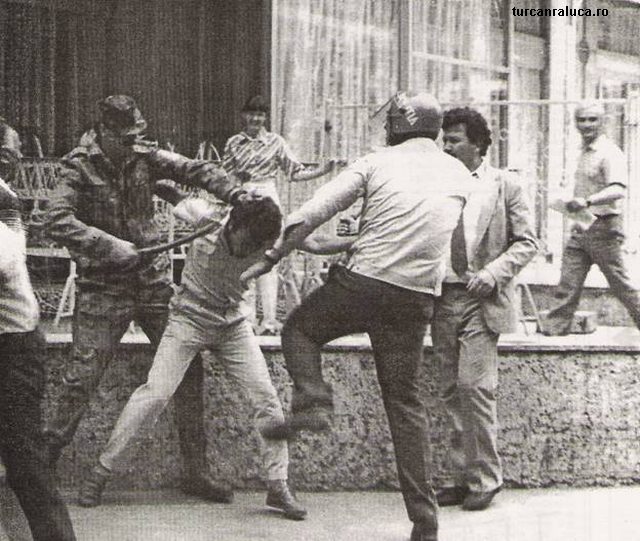

violent outbursts of June 13-15, 1990, having miners’ arrival in Bucharest as

their momentum as well as the miners’ lashing out at Romanian capital city’s

civilian population meant that Romanian society was backtracking on democracy,

within six months since Romanians had regained their freedom in December 1989.

The events back then proved that a society that had freshly emerged from a

totalitarian political regime still had the demons of the past to fight before

it healed completely. In June 1990, it was for the third time that Bucharest

had been stormed by the miners, in a bid to back the then National Salvation

Front against opposition parties. Among other things, miners’ riots were in

fact a manifestation of hatred and intolerance against democratic pluralism

which at that time was very difficult to become functional in Romania. Against

the backdrop of the protest rallies mounted by the Opposition in April 1990 and

in the aftermath of the election held on May 20, 1990, won by the National

Salvation Front, tension was literally spiraling. On June 30, 1990, the state

institutions tried to quash the protest rallies in University Square, which was

the beginning of three-day long violent clashes that eventually claimed the

lives of 6 people, leaving 750 other wounded.

What

happened over June 13-15 was a one-of-a-kind event. The historian Cristian Vasile told us what was so very unique about that

event.

Some of the historians placed it against the backdrop of the time span

that occurred immediately after communism in Romania, describing it as the last

repression of a communist origin ever to have been staged in the country. And

they are right, I think, because manifestations back then, consisting in the

reprisal of part of the civilian population, have certain points in common with

what happened in national history immediately after 1944. An explanation of

that could be the fact that the political staff and political practices of

March, 1945, continued even after that date. The common political practice of instigating

civilians against one another was also implemented in June 1990.

It has

been said that miners’ riots of June 1990 were made possible by the state

institutions being weak, by the riot police failing to quash protest rallies on

June 13.

Historian Cristian Vasile:

I also tend to believe in the theory of the riot police being weak and

unable to contain certain forms of popular unrest. If we have a closer look at

how things developed over June 13 and 15, mostly on June 13 as that is the

climactic day, we can indeed see the riot police slackening, but there are also

a couple of issues that have been hitherto unexplained. There are several recordings,

real recordings, there are those radio interventions of then the deputy

Interior Minister, general Diamandescu, who said something like we are going

to set the buses ablaze, as agreed, to the recipient of his messages. What are

we to make of that kind of exchange? Then there are concordant testimonies

whereby there were not the rioters who set fire on the police building in the

capital city, but the building was set ablaze from the inside. Also unexplained is how hundreds of policemen retreated with no defense, leaving

the Interior Ministry building also unprotected.

The

new power embodied by Ion Iliescu had to be strengthened through the

manipulation of the crowds, so most of those who analyzed miners’ riots view

that as a meaningful explanation of events back then.

Historian Cristian Vasile:

The unrest that flared up in University Square and Victoria Road was

quashed around midnight on the night to of June 13 and all through to 3 am, on June

14. Riot police managed to have everything under control, rioters had been

arrested. The miners came a little bit later, they were welcomed by the then

president Ion Iliescu. Instead of defusing the tension, telling the miners the

army and the police had everything under control, Ion Iliescu invited them to

occupy University Square. What was the purpose of such a move, since a couple

of hours earlier the police and the army totally controlled the situation? That

utterly reckless invitation led to the violent clashes that broke out on June

14, in the morning, and on the following day. So all in all, it was an

absolutely pointless instigation to violence, a criminal act which was worthy

of the Criminal Code.

The miners’ riots of June 1990 were one last

convulsion of the communist mindset, in a society that had but newly emerged

from the collapse of the communist regime in December 1989.

Cristian Vasile:

Why the miners? Attempts were made with other categories of workers,

even over June 13 and 14. There is official evidence of a call being made for

workers from Bucharest, of several factories and plants, of the August 23 Plants

and suchlike. Quite a few of the unions turned down the proposal and refused to

intervene, on the grounds that the conflict was of a political nature and it

was not for them to set things to rights. Yet it appears that the miners as a

category were more receptive to the propaganda of the then National Salvation

Front, of Iliescu’s regime. As for Ion Iliescu, he has been defending himself

claiming he did not make his call to the miners alone, but to all responsible

social forces. But that is an aggravating circumstance for somebody who is the

president of a country. And it is here that the tragedy of those episode lies,

there was the buoyancy of part of the Bucharest population who literally gave

miners rounds of applause for what they were doing. And what they did was to

beat young students to a pulp, as well as bearded men or women wearing

mini-skirts. Which was a stark reminder of Ceausescu’s policy, of rockers being

hunted in the 1970s.

The

price Romania had to pay for miners’ riots of June 13-15, 1990, was its own

international isolation. Specifically, that meant the agreement with the IMF

being frozen, but also the impossibility to contract another loan.

Politically, miners’ riots of June 1990 stalled Romania’s gaining accession to

the Council of Europe. It was not until 1993 that Romania became a member of

the Council of Europe, much later than many other countries of the former

Soviet Bloc.

(Translation by Eugen Nasta)