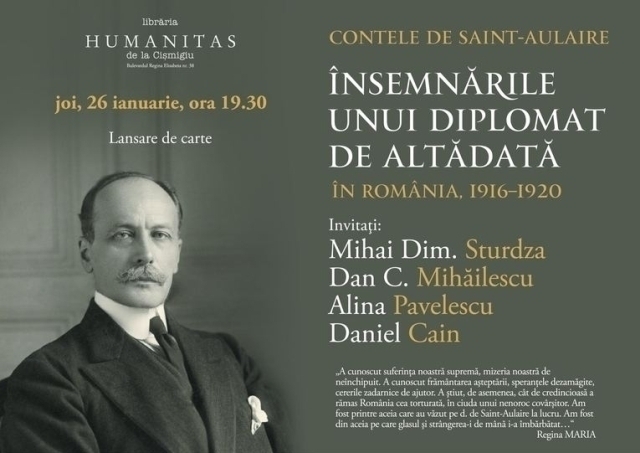

Auguste-Felix-Charles de Beaupoil, Count of Saint-Aulaire, was born

in 1866 and died in 1954. He arrived as ambassador to Romania in the troubled

summer of 1916, when Romania joined the fray in WWI. He wrote his recollections

of that time in a book called Notes of an Ambassador of Yore. In Romania,

1916-1920. The book is one of the most important and poignant sources

documenting political games and tragedies that occurred towards the end of the

war. He loved Romania, was an anti-communist and advocated Romania’s joining

the war. He had a sharp analytical spirit, and was a visionary when it came to

the course of history.

Historian Alina Pavelescu recommends that we read Saint-Aulaire’s

book twice:

The first fragment I read

tells about his visit to the office of Aristide Briand, before going to

Romania, and he says about the latter that ‘the man’s desk was as bereft of

papers as his own head was of ideas’. Right away I started liking him a lot,

and I thought that he deserved the gratitude of everyone who puts off forever

putting order in the papers on their desk. I recommend that you read this book

twice. The first reading is very easy for us Romanians, because it is favorable

to us. It is more favorable to us in many situations than the memoirs of many

Romanians of the time, because this Saint-Aulaire loved Queen Marie of Romania.

He says extraordinarily beautiful things about the Romanians’ capacity for

sacrifice, and their generosity in sacrifice. He speaks about the Romanian

political class in terms that we are not used to. It is flattering to read

Saint-Aulaire when he says these things about Romanians, considering how

critical he was the of the French political class.

The Count of Saint-Aulaire showed remarkable understanding of the

world in which he arrived. Alina Pavelescu believes that the second reading

helps us see better into the writer’s observations:

I recommend a second reading,

because the Count of Saint-Aulaire is only in appearance an easy source to

identify within that landscape. Why? Because he is an aristocrat representing a

republic, he is a conservative who is a diplomat on behalf of a left wing

government, he is a civilian who feels boxed in, alongside many others, in an

environment dominated by the army, by soldiers and their logic. We know how the

story ends, but when we read his memoirs, we don’t know how it all ends. It is

true that he writes in 1953, he is saddened by the fate of Greater Romania, he

has confirmations regarding the harsh judgment he issued after WWI. He doesn’t

know, however, how the world ended up after the success of the USSR in WWII.

Every time, the reader is taken through several stages in which we don’t know

how the story ends. Being French, he came from a society which, at some point,

was much more favorable towards the Russians than towards Romanians. The French

loved the Russians, maybe they still love them, much more than we Romanians

ever loved them. Saint-Aulaire does not have the sin of Russophilia, I would

say rather the opposite, he had no illusions about Tsarist Russia either when

he dealt in Bucharest with Russia’s representatives negotiating Romania’s entry

into the war.

Literary historian Dan C. Mihailescu told us about the way in which

others saw Saint-Aulaire:

I. G. Duca knows very well

how to carry himself around diplomats, he is very clever in reading their

gestures and their words, and compares Russia’s Poplevski, who was discredited

by his fellow Bolsheviks, to Britain’s Lord Barclay, who was under the

influence of Jean Chrissoveloni. And he writes about Saint-Aulaire: ‘My God,

was that man honest!’. Like all Frenchmen, he didn’t know how to adapt. To

adapt to the transactional nature of Romanians, to their two faced nature, was

very hard for him. Poor Saint-Aulaire, he didn’t know how to maneuver among

Marghiloman’s and Carp’s conservatives,

who were Germanophile, and the Francophiles Bratianu, Duca, Queen Marie and

Barbu Stirbey. Little by little, Duca showed him how to adapt to expectations,

and the Frenchman became an expert in the mercantile psychology of Romanians.

As we can see in these memoirs, the Count of Saint-Aulaire was a

visionary, he had the ability to anticipate the failure of communism, as Dan

Mihailescu told us. Saint-Aulaire’s book is a book written by a man who

understood the world he lived in, and who saw into the future.