Dans les années 1930, un berger du village de Maglavit, situé sur les rives du Danube dans le sud-ouest de la Roumanie, prétendait que Dieu lui avait apparu et parlé directement. Effrayé au début, mais gagnant ensuite du courage, le berger a raconté aux villageois le miracle dont il avait été le témoin et leur a transmis le message de Dieu. Cest ainsi que naquit le phénomène de Petrache Lupu, personnage mystique et guérisseur, qui allait faire la une des journaux et des magazines illustrés pendant longtemps. Il est rapidement devenu l’une des personnalités publiques les plus populaires, plutôt en raison de l’appétit de toute société pour le sensationnel que grâce à ses actions ou à sa personnalité.

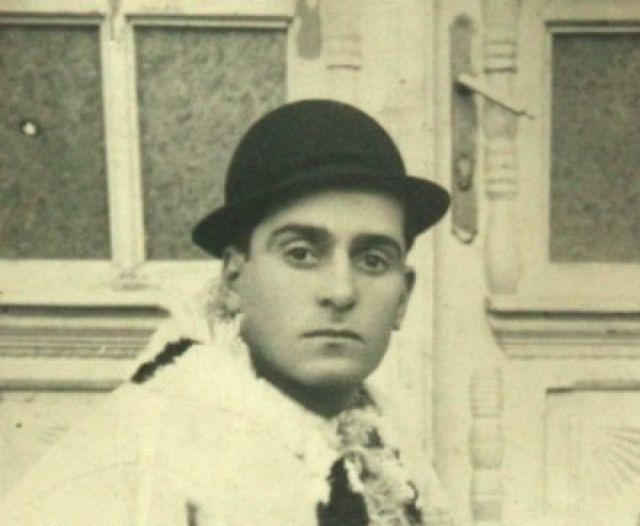

Petrache Lupu était un paysan quelconque, né au début du XXe siècle, en 1907. C’était l’année marquée par la dernière émeute paysanne d’Europe, une révolte qui allait apporter de nombreux changements législatifs et améliorer la vie rurale. Les valeurs modernes, que les Roumains avaient commencé à adopter depuis les années 1820, avaient mis du temps à atteindre aussi les villages, où elles avaient du mal à être considérées comme un mode de vie. Dans les campagnes, les superstitions restaient très fortes malgré une présence constante de l’Église, et dans ce contexte, la transformation de Petrache Lupu en sauveur ne fut pas une surprise.

Orphelin dès l’âge de 5 ans, Lupu a été élevé dans plusieurs familles du village. Il n’a reçu aucune éducation scolaire, il ne savait ni lire ni écrire et son vocabulaire était basique. Le magazine hebdomadaire «Realitatea ilustrată/La réalité illustrée», qui, en juillet 1935, publiait un log article au soi-disant «miracle de Maglavit», notait que le berger avait des troubles de l’audition et de la parole, suite à la rougeole, quil avait contractée à un moment donné. Le jeune homme était décrit comme quelquun de réservé, sans être un solitaire. Il avait réussi à fonder une famille, à avoir une femme et deux enfants. Les 31 mai, 7 juin et 14 juin 1935, sur la route de la bergerie, Lupu aurait vu un vieil homme flotter au-dessus du sol. L’historien Roland Clark, qui étudie le phénomène religieux dans la Roumanie de l’entre-deux-guerres, travaille sur un volume dans lequel il analyse également le célèbre cas de Petrache Lupu, le héros de l’histoire de Maglavit : «Petrache Lupu était un berger qui a vu Dieu, en 1935. Il l’a vu 3 fois. La première fois, il a dit qu’il l’avait vu comme un vieil homme, qui sentait une certaine odeur. Il est allé raconter tout ça à son prêtre et, ensemble, ils ont établi que le vieil homme sentait lhuile sainte. Ses cheveux le couvraient de la tête aux pieds. Ce vieil homme a dit à Petrache Lupu qu’il était Dieu et qu’il voulait que Petrache exhorte les gens à se repentir, à aller à léglise, à ne plus jurer, à ne plus pratiquer lavortement, à faire sonner les cloches et à ne pas travailler les jours saints. »

Petrache s’est rendu au village, où il a raconté au prêtre lextraordinaire apparition dont il avait été le témoin. Le pope l’a cru sur parole et, ensemble avec leur communauté, ils ont fait connaître leur village dans tout le pays. Roland Clark : «Lupu a reçu le soutien du pope du village et de l’évêque, ces deux derniers ayant gagné beaucoup d’argent. Des gens de tout le pays ont envoyé de l’argent à Maglavit, mais on ne sait pas combien en est arrivé à destination, ni combien sen est perdu en cours de route. Les gens ont découvert que Petrache Lupu avait le don de guérir certaines maladies, des paralysies, des troubles de la vue et du langage. On dit qu’il avait lui aussi un trouble du langage, mais selon certains il aurait été tout simplement muet. Des dizaines de milliers de personnes sont venues en pèlerinage dans ce petit village, ce qui a beaucoup inquiété les médecins. Le fait d’avoir beaucoup de malades dans un endroit serré, où il n’y avait pas beaucoup d’habitants, pouvait déclencher une crise sanitaire majeure. De plus, quelqu’un qui disait que l’on pouvait guérir par la foi pouvait influencer les gens à ne plus vouloir consulter un médecin. De toute façon, peu de gens chercher le conseil dun médecin, à l’époque. Ils faisaient plutôt confiance aux guérisseurs et à quiconque, sauf aux médecins. »

Une déferlante de personnes souffrantes sest ruée sur le village de Maglavit, qui leur donnait de l’espoir. On dit qu’environ 2 millions de personnes sont aller voir le «Saint de Maglavit», en quête de guérison. Roland Clark déclare que beaucoup y ont trouvé leur compte et que le berger mystique était un cas typique, montrant le niveau d’éducation de certains segments de la population à cette époque-là : «Cette affaire montre tout ce que les gens pensent de la religion et des superstitions, de la science, de la médecine et de la politique. Le Mouvement Légionnaire, dextrême droite, a lui aussi essayé de s’y infiltrer, de se rapprocher de Petrache Lupu, tout le monde en était impliqué dune certaine manière et avait quelque chose à dire sur cet homme. En regardant cet homme de plus près, nous pouvons mieux comprendre la culture rurale roumaine des années 1930. Le mouvement « Oastea Domnului / l’Armée du Seigneur » a beaucoup soutenu Petrache Lupu, les néo-protestants ont dit que ce n’était pas bien de faire cela, ils ne lui faisaient pas confiance, pour eux il n’était qu’un charlatan et un imbécile. Mais l’Église Orthodoxe l’a soutenu. »

Petrache Lupu est décédé en 1994, dans son village natal, à l’âge de 87 ans. Il a laissé derrière lui une légende et un monastère ouvert en 2019. (Felicia Mitraşca)