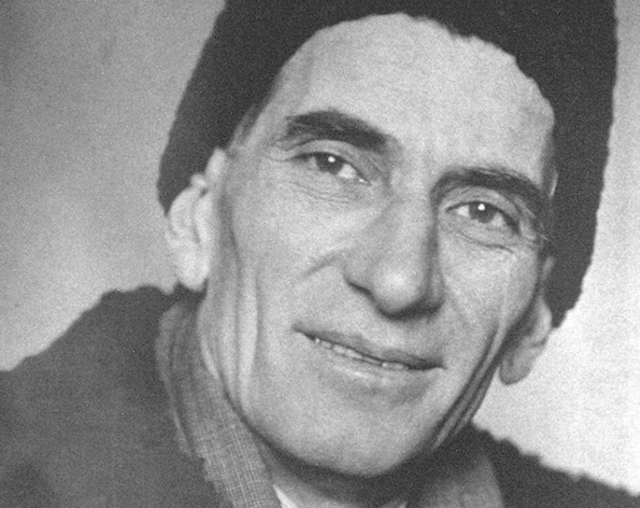

During their lifetime, people may reach some of the most unexpected places and become witnesses to events they never thought they would witness. This is the case of the centenarian general Titus Gârbea, ‘a Romanian in northern Europe who witnessed the history of that region in the first half of the 20th century. Gârbea was born in 1893 and died in 1998, at the age of 105. He fought in World War I and was appointed military attaché in Berlin between 1938 and 1940, and from 1940 to 1943 he was military attaché in Stockholm and Helsinki. He served on the front in World War II, was decorated, and in 1947 he was put on a reserve duty status. From his position as diplomat, he was in contact with several personalities in the history of northern Europe such as King Gustaf V of Sweden and Alexandra Kollontai, the Soviet ambassador to Stockholm.

The Oral History Center of the Romanian Radio Broadcasting Corporation had the opportunity to talk to Titus Gârbea in 1994, when he was 101 years old. The general recollected the moment when King Carol II appointed him Romania’s representative to Scandinavia: Finland is a small country, with four million inhabitants, but with hardworking and honest people, true to their word. King Carol II called me and said, Could you go to the Nordic countries ?! I was in Berlin on a very difficult mission, and at the same time I had missions in Bern, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. I said, Your Majesty, I can cope with the mission, but travel will be very expensive, because I will often have to travel by plane! And so, I was also appointed military attaché in the Nordic and Baltic countries, that is, about five or six more countries were added. I was always on the road! But I coped with the mission and sent very important information for our country and its future, because the Nazi danger had begun threatening our country too.

Already familiar with the Nordic spirit, Gârbea travelled between the Swedish and Finnish capitals. But, in the Baltic States, occupied by the Soviets in 1940, he was not received in a way that he had expected: “My job required me to go to both Stockholm and Finland from time to time. The mission was very difficult, because Berlin was in control of the entire Europe. I was assigned to the four Nordic countries: Denmark, Sweden, Finland and Norway. Additionally, I was also dealing with the three Baltic countries where we were seen as a black beast by the communists in those three countries. Our very good Estonian friends warned me: ‘Sir, don’t leave the house at night because the Russians, who are almost everywhere, are capable of doing very wicked things! Well, I survived, nothing happened, but I was the black beast.

The eve of World War II caught Gârbea right on the demarcation line between the Poles and the Soviets who were ready to occupy Poland. There he became aware of the Soviet antipathy to the Romanians: In 1939, after Hitler’s Germany and Lenin’s Russia, side by side, simply crushed Poland, I was right there on the front. I went to Brest-Litovsk where the Russians were supposed to come. According to them, Brest-Litovsk was to remain in Russian hands, and the rest, in the west, in the hands of Germany. And when I arrived in Brest-Litovsk and got in touch with the Russians who had come there, given that we, as diplomats, had some freedom, one of the Russians, with a typically Russian rude attitude, told me: ‘You are going to have the same fate one day. He literally threatened me, despite my position of military attaché. I did not retort to his rude attitude. And indeed we had the same fate.

In the same turbulent year 1940, Gârbea was in Sweden when the winter war between Finland and the Soviet Union began. Little Finland showed extraordinary heroism in the face of the Soviet giant that had invaded it. Gârbea wanted to highlight the Finnish courage and the sympathy that the whole world showed to the Finnish people: I was in Stockholm and Finland when this war broke out. From there I was following the Russian operations in Finland, during that very hard winter in 1939-1940, when the natural ally of Finland helped it a lot in the battle. But in the spring, when the thaw began, the huge number of big aircraft overwhelmed the poor Finland with a population of only four million. It was like a mosquito fighting a stallion! Because at that time, I must say, Russia was blamed and ostracized by the whole continent for what it had done, for having attacked poor Finland, with considerable troops, to occupy everything. It was nothing but one of the many horrendous actions taken by Russia, actions also taken against Romania, in 1877 and before.

The Romanian Titus Gârbea witnessed history far from his country. But it was an equally personal history. (LS)