Romanian society had stepped up its

modernization process and its orientation towards the West in the second half

of the 19th century. Ever since, women’s right have been subject to

debate in Romanian media. Such a valuable initiative was made possible thanks

to the activity of several feminist associations which at that time took

affirmative action in support of women’s rights to education as well as for

women’s right to vote. Accordingly,

through the initiative of several women intellectual women, women in their

entirety began questioning their traditional role which granted them limited,

if any, access beyond the private sphere. Feminist activist women also sought

to influence the public sphere. Among them, journalist, translator and novelist

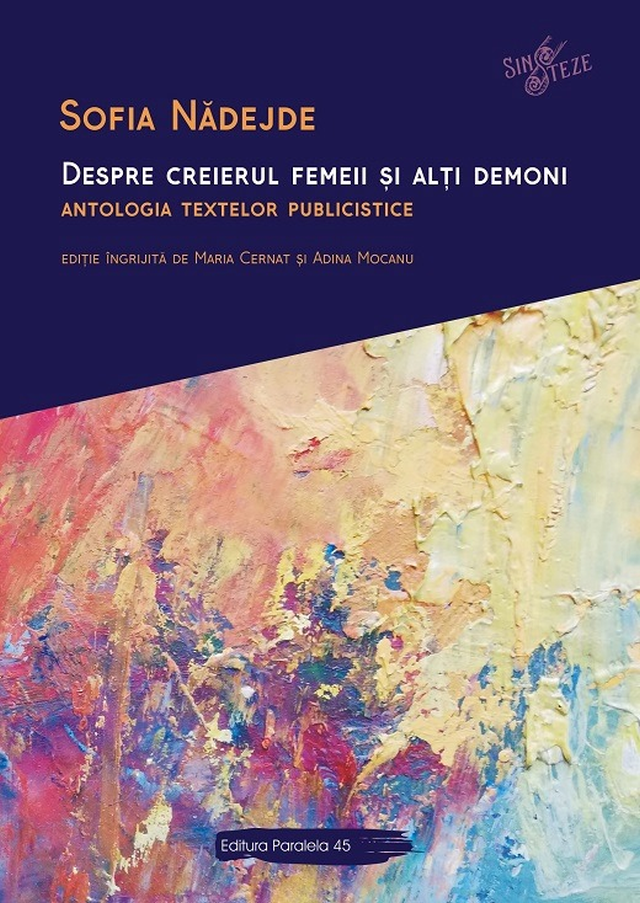

Sofia Nadejde, who was born in 1856 in Botosani. A collection of her feminist

articles has recently been brought out by the Paralela 45 publishers. The

volume is titled About a woman’s brains and other demons and was jointly

edited by Maria Cernat and Adina Mocanu.

Maria Cernat:

She fought her battles

on several fronts at a time. Apart from the fact that the family she had can

today be viewed as successful and numerous, as she had four girls and two boys,

plus another girl who had died in early childhood, all her children had

exceptional career. Furthermore, Sofia Nadejde was an activist woman and she

wouldn’t have favored being presented as a successful woman in the lifestyle

magazines of her time. She was a serious woman, extremely focused in her

observations and studies and was very close to the life of the poor simpletons.

She would have liked it a lot to emancipate herself alongside all women in

Romania. She wasn’t fighting for the rights of privileged women. That is why it

seems a little bit odd she did not fight for women’s right to vote because,

given the census suffrage was in place, the right to vote would have been

granted to a very limited number of women. Only the well-to-do had the right to

vote back then. Reason enough for Sofia Nadejde to pledge she was interested to

fight for all women and not for the privileged ones.

Some of women intellectuals who in the 19th

century took affirmative action for the emancipation of women advocated the

idea that, notwithstanding, women had to retain their traditional role yet some

extra rights should have been granted to them. Sofia Nădejde wanted a thorough

change of that paradigm. And it was not only that that set Sofia Nadejde apart

from the vast majority of the intellectuals of her time. Herself and her

husband, Ioan Nadejde, were adepts of socialism, a marginal ideology in

Romania, at that time.

Maria Cernat:

She made her debut in

socialist magazines that today maybe be described as feminist. One of them was

The Romanian woman, and then she contributed to The Contemporary for a long

time. That mainly happened in the last years of her life when she mainly wrote

texts firmly supporting women’s rights. She shifted her focus to writing

literature and, using literary means of expression, she did what is today known

as art for social purpose. Herself and her husband Ioan Nadejde, assumed art

for social purposes together with other socialists of her time, such as Constantin

Dobrogeanu-Gherea. So initially, Sofia Nadejde dealt with women’s rights, with

women’s status in Christianity, prostitution, the situation of the family,

there were issues having to with political philosophy. Then Sofia Nadejde

prioritized her literary activity, without however ignoring her socialist

ideology. She advocated women’s right to work, their independence, and not only

the legal one, their education. According to Sofia Nadejde, women’s education

went beyond the purpose of turning them into mothers who were capable of

raising the children of the nation. Sofia Nadejde also took affirmative action

for women’s economic independence, for their right to have a job and financial

autonomy.

Nevertheless, there were not just those ideas

alone by means of which Sofia Nadejde stepped out of the line, being a

one-of-a-kind personality in her time.

Maria Cernat:

The funny thing was that she

also contributed articles with apparently very conservative principles. For

example, she was against dancing. She described it as being a primitive habit, a

habit of the savages. She was against preening. In today’s parlance, we could

say, being somehow anachronistic, she was actually against relative beauty

standards. She also criticizes balls, she did not favor balls where people gathered,

danced and then caught pneumonia as they were in a sweat going out in the cold

weather outside. She also have principles that today may seem conservative, yet

she advocated them as being part of women’s emancipation, She did not think

emancipation meant smoking cigars or going to the pub to get drunk or to have

many lovers. In other words, you shouldn’t do what men did. For her, that was

not emancipation. Instead, taking responsibility for the education of children

as seriously as possible, that, for her,

was a perfect example of emancipation.

Obviously, Sofia Nadejde’s principles drew

her into all sorts of polemics, the most famous being that with Titu Maiorescu,

a minister, a conservative MP, a philosopher and a literary critic, a towering

figure in Romanian culture, past and present.

Maria Cernat:

There’s another interesting

episode, when Sofia Nadejde contradicted Titu Maiorescu as regards the weight

of women’s brain. He disapproved of the idea whereby the fate of the nations be

left entirely up to human beings whose brain is 10per cent lighter than men’s

brain. If their brain is smaller, the conclusion we must draw from that is that

all women are less capable than men, intellectually. So, according to

Maiorescu, we need to adopt the sphere separation principle: women should remain

in the domestic sphere, while men should dominate the public one. Sofia Nadejde

pointed to the fallacy he committed: making sheer weight the equivalent of

intelligence, that might lead up to the conclusion that the whale is smarter

because her brain is big and heavy.

In

1903, the novelist Sofia Nadejde scooped the Universul daily prize in 1903. The

editor in chief of a magazine, a translator and a columnist, Sofia Nadejde died

in 1946. Many of her ideas remain up-to-date to this day.