Zu Beginn des 18. Jahrhunderts wurde in der entsprechenden Gegend eines der schönsten Klöster Osteuropas, das Văcărești-Kloster, errichtet, das nach der Machtübernahme durch die Kommunisten in ein Gefängnis umgewandelt wurde.

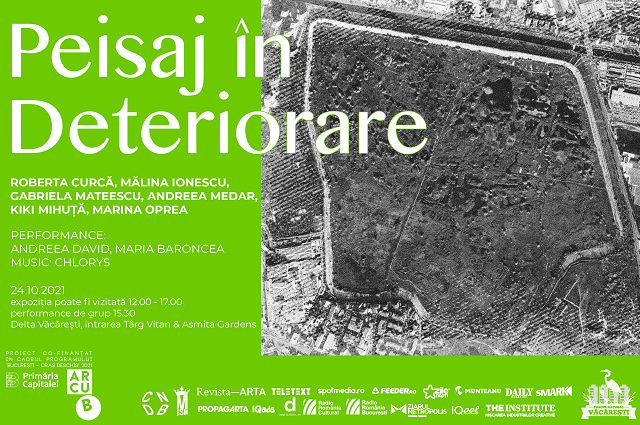

Trotz zahlreicher Proteste von Persönlichkeiten aus dem Kulturbereich wurde das Văcărești-Kloster 1986 auf Anordnung des kommunistischen Präsidenten Nicolae Ceaușescu abgerissen. Einigen Restauratoren gelang es, die Fresken und Ikonen, die das Kloster schmückten, zu retten. Die Besitzer von Grundstücken und Häusern in dem Gebiet wurden enteignet, und das kommunistische Regime begann mit umfangreichen hydrotechnischen Arbeiten, die schließlich aufgegeben wurden. Nach Berichten über das Vorhandensein einer beeindruckenden Anzahl von zum Teil seltenen Vogelarten und einer ausführlichen Fotodokumentation hat sich ein Team von Naturschutzgebiets-Experten 2012 an die Einrichtung eines Naturparks gemacht.

Heute ist der Naturpark Văcărești dank des Ökosystems, das sich in unmittelbarer Nähe des Zentrums der Hauptstadt gebildet und entwickelt hat, eine der touristischen Attraktionen in Rumänien. Der Dokumentarfilm Delta Bucureștiului wurde in Rumänien auf dem TIFF (Transilvania International Film Festival, Cluj-Napoca) uraufgeführt, kam Ende September in die rumänischen Kinos und soll im kommenden Frühjahr auch in Frankreich Premiere feiern. Wir sprachen mit der Regisseurin Eva Pervolovici über die sehr persönlichen Memoiren – sie habe sich durch einen Wandteppich inspirieren lassen, den sie von der Künstlerin Lena Constante erhielt, die 1954 zu 12 Jahren Gefängnis verurteilt wurde.

Alles begann mit diesem Wandteppich von Lena Constante, einer Freundin der Familie, die in den 60er Jahren in Văcărești und anderen Gefängnissen in Rumänien inhaftiert war. Dieser Wandteppich war für mich wie ein Ruf aus der Vergangenheit, er löste mein Bedürfnis aus, mehr über die Geschichte dieser inhaftierten Frauen zu lesen und ihre Geschichte zu dokumentieren. Der Wandteppich hat mich auch neugierig gemacht, und so stieß ich auf das Buch <Die stille Flucht> von Lena Constante, und dank dieses Buches entdeckte ich, dass es noch andere Frauen gab, die in Văcărești inhaftiert waren, und einige von ihnen schrieben auf den ersten Blick merkwürdigerweise auf Französisch und veröffentlichten ihre Memoiren in Frankreich. Wir müssen jedoch bedenken, dass diese Bücher vor 1989 geschrieben wurden und die französische Sprache für diese Art von Memoiren sicherer für den Autor war. Ich möchte Adriana Cosmovici erwähnen, die das Buch Au Commencement etait la fin (1951) schrieb, das beim Humanitas-Verlag unter dem Titel

Adriana Cosmovici gelang in den 60er Jahren die Flucht nach Frankreich, also während des repressiven Regimes von Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, bevor Ceaușescu an die Macht kam. Auch in Frankreich war es damals nicht ganz einfach, denn nicht nur die Franzosen, sondern die meisten Menschen im Westen hatten eine gute Meinung vom Kommunismus und hielten Andersdenkende für Faschisten. Umso wichtiger war die Hilfe von Monica Lovinescu, einer bekannten Produzentin bei Radio Freies Europa, die Lena Constante in jenen Jahren in Paris unterstützte. Neben den Büchern von Lena Constante und Adriana Cosmovici werden in der Dokumentation auch Zitate aus dem Roman <Le cachot des Marionettes – quinze ans de prison> / <Das Marionettengefängnis>.”

Man kann sich nirgendwo verstecken, wenn die Geschichte hinter einem her ist”, sagt die Erzählerin des Dokumentarfilms Delta Bukarest an einer Stelle, ein Satz, der ein mögliches Motto für den Film sein könnte. Eva Pervolovici habe sich bei ihrer Recherche auf die Erinnerungen der Häftlinge konzentriert.

Auf diese Weise wurden die Informationen zusammengetragen, und der Film konzentriert sich auf die Aussagen der Frauen, obwohl das Gefängnis von Văcărești einen Flügel hatte, in dem auch Männer inhaftiert waren. Ich habe mich für einen Film entschieden, der auf den Erinnerungen der weiblichen Gefangenen basiert, weil ich das Gefühl habe, dass ihre Stimmen immer noch nicht genug gehört werden. Wir sprechen viel über Kriegshelden oder Helden des antikommunistischen Kampfes und fast nichts über Frauen, die ebenfalls enorm gelitten haben, oft aus einem nicht existierenden Grund. Einige von ihnen wurden einfach deshalb inhaftiert, weil sie sich zur falschen Zeit am falschen Ort befanden, wie Lena Constante, die nicht einmal politisch engagiert war.

Ich hielt es für wichtig, diese Zeugnisse von Frauen, die gelitten und überlebt haben, aufzubewahren, denn es sind die Zeugnisse von sehr starken Frauen, von Kämpferinnen, die es geschafft haben, sehr harte und ungerechte Momente zu überwinden und am Ende etwas Gutes daraus zu machen. Dies war der Fall bei Lena Constante, die für ihre schriftlichen Zeugnisse, aber auch als bildende Künstlerin durch die von ihr geschaffenen Wandteppiche bekannt ist. Deshalb hat der Film auch etwas Optimistisches und Positives an sich, er erzählt von der Überlebenskraft dieser Frauen. Ich würde sagen, er ist auch eine Lektion darüber, wie wir sehr schwierige Momente im Leben überstehen können, indem wir das Beste aus diesen Erfahrungen machen.”

Eva Pervolovici ist auch die Regisseurin von Marussia, ihrem Spielfilmdebüt. Der 2013 erschienene Film wurde mit zahlreichen internationalen Preisen ausgezeichnet.