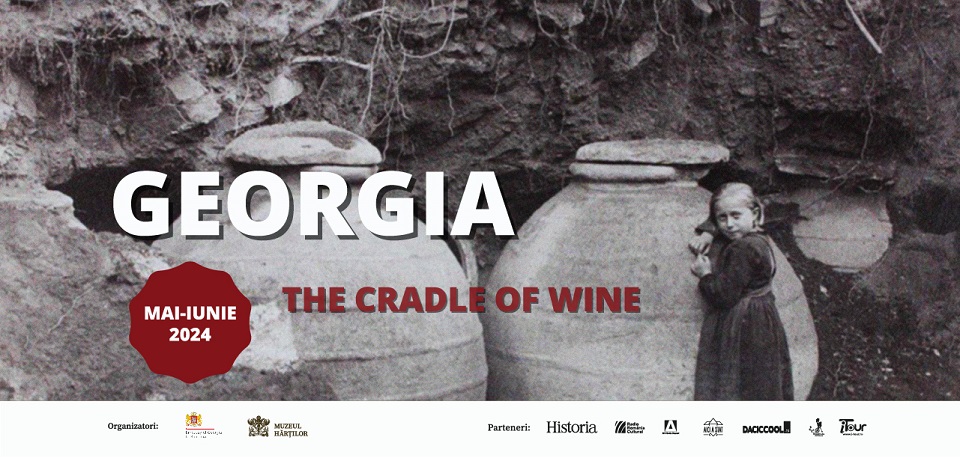

Georgia’s ancient wine-making culture is in the spotlight as part of an exhibition hosted by Bucharest’s Museum of Old Maps and Books.

In an exclusive interview to RRIs Eugen Cojocariu, ambassador Tamar Beruchashvili has spoken about the exhibition.

Georgia’s ancient wine-making culture is in the spotlight as part of an exhibition hosted by Bucharest’s Museum of Old Maps and Books.

In an exclusive interview to RRIs Eugen Cojocariu, ambassador Tamar Beruchashvili has spoken about the exhibition.

A Romanian consumes an average of 2.5 bottles of wine per months, which means 23.5 liters per year. The figures have stabilized in recent years, and represent an increase compared to the 2015-2017 period, the International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV) shows. Romania is ranked 13th at global level in terms of wine consumption per capita – a little over 23 liters per year, 30 bottles per years and 2.5 per month. Portugal leads the standings as the world’s largest producer and consumer with 52 liters per year (6 bottles per month). The list continues with France and Italy, two countries with a long history of wine-making. There is virtually no launch or dinner served in France without a glass of wine.

In Romania, differences between urban and rural communities are quite large, as people in rural areas prefer to drink other types of beverages or homemade wine. Still, for bottled wine aficionados, the shape and color of wine bottles carry special meaning, says George Ignat, also known as George Wine, a lecturer with the Superior School of Sommeliers, a member of the Wine Lover Romania Association.

“When we’re in a restaurant, or perhaps in the wine aisle at the market, we’re surrounded by a plethora of bottles that come in scores of shapes and colors and display various labels that are a genuine sight for the eyes. Color-wise, bottles come in a diverse offer. The most common are transparent bottles, used in particular for white and rosé wines. Then there are brown bottles, which are usually used to bottle red and green wines, although they are also used by white wines. For advertising reasons, winemakers also sell wine in blue bottles or resort to other less conventional tones. In terms of size, things get even more interesting. A typical wine bottle has 750 milliliters. I will try to outline the main types of wine that are bottled in atypical bottles. There are many smaller-sized bottles, but the most frequently used has 375 milliliters, which is half the standard volume of standard sweet desert reds from Soter. Why this specific figure? Whereas the typical yield for these sweet wines is 65%, due to atypical production process, the yield is 12%, production is quite small, which is why this type of bottle was adopted. The standard 750-mililiter bottle actually has 770 milliliters of liquid inside, due to the cork and the oxygen in-between”.

George Ignat also spoke about other types of non-standard wine bottles.

“We also have a 1.5-liter bottle, which is the most widespread of larger bottles. You can notice that every variant is in fact a multiple of 750 on the wine-bottling scale. Then we have the 2.25-liter bottle, the equivalent of three standard bottles, also known as Marie Jeanne, the 3-liter bottle, Jéroboam, the 4.5-liter bottle – Réhoboam, the 6-liter bottle – Mathusalem, the 9-liter bottle Salmanazar, the 12-liter bottle – Balthazar, the 15-liter bottle (the equivalent of twenty standard bottles), known as Nabuchodonosor”.

The shape of bottle wines is also steeped in meaning, says George Ignat.

“In terms of shape, we have three different standards – the Burgundy bottle, also known as Bourguignon, devoted to wines from Bourgogne, which appeared at the end of the 17th century. It has a narrow neck and is cone-shaped. It has a ring in the upper side which the glass blower adds at the end. The Bourguignon bottle is the French standard by excellence. Nearly all Chardonnays are bottle in this Burgundy bottle. Then, there’s the Bordeaux bottle, which also references a French wine-making area of legend. It is rather tall, with a fairly narrow neck, because corks used to be smaller, 18 millimeters in diameter compared to 24 in the present-day, with marked shoulders weighing down on the bottle’s cone shape. The shoulders were specifically designed to help the wine settle. The Alsace bottle, is very refined and elegant, and is also known as Flute d’Alsace, being the tallest of all bottles. Its trademark dates back to 55 years ago. It is reserved for wines made in Alsace. Various wine-making regions of France have their own dedicated bottles. Let me give you just one example – in Provence, the Haute Winery is famous for having manufactured its own bottles, now adopted by many producers of Provence rosés. This model used to be shaped like an amphora, and was patented in 1923”.

While there are hundreds of types of wine bottles, most wine producers today use one of the three standard bottles: the Riesling (Alsace) bottle, the Bordeaux bottle or the Burgundy bottle, which you can all see on supermarket shelves. Yet regardless of shapes and sizes, the number one rule of drinking wine is, of course, moderation. (VP)

Wine

enjoys a long tradition in Romanian space, with viticulture being attested as

an activity of the ancient Dacians. The Greek historian Strabo, who lived over

the 1st century BC and 1st century AD, writes that the

Dacian king Burebista had ordered vineyards to be burned in order to discourage

wine consumption. Beyond Strabo’s frivolous remark, historical sources

frequently mentions the presence of wine-making in the area north of the Danube

river.

The

history of wine over 1945-1989 was marked by centralized economic measures

affecting the production and trading of wine. Marian Timofti is the president

of the Organization of Sommeliers from Romania. He told us more about the

guiding principles of wine-making.

Wines

produced in Romania back then were meant to cover export-related debt, in the

sense that harvests had large volumes. The larger the quantity of grapes, the

lower the quality of wine. As the minerals the vine draws from the ground are

divided to a larger or smaller number of grapes, the larger or smaller their

presence. Therefore, the body of the wine, its flavor, its scent, the anthocyanins,

which also affect the pigments, will have a lower presence. But this was the

practice back then, as 80-90% of the wine was export-bound. The wine sold would

cover large quantities of Romania’s debt. The number one importer was the

Soviet Union, which wanted wines with residual sugar – semi-dry or semi-sweet

wines, because the cold in the USSR demanded a high energy consumption rate in

individuals. Secondly, the alcohol of wines was not supposed to exceed 12.5%,

and we would laugh back then that it didn’t have to compete with the vodka.

Romania’s viticulture was doomed by Nicolae Ceaușescu. We’re talking about quality viticulture,

because heads of farms and vineyards were paid depending on the production per

hectare. Whether it was wheat, corn, grapes or other harvests, they were paid

depending on volume. Both the reports and harvests had to be high.

Nevertheless,

Romania used to have quality wines that few people had access to. These were

exceptional wines that took part in international competitions.

Romania

was known worldwide as a maker of quality wines in limited edition, made from

selected parcels. These were selected from every vineyard before the

wine-making process, which we would call the small barrel. The wine itself

was reserved for special social categories. They were sent to international

contests, which Romania won quite often. In terms of imports, Westerners

refrained from importing from Romania, since the wines available were made from

large volumes, they were not medal-winning wines.

One

of the fabrications of Romanian oenology back then was the so-called Ceaușescu’s wine. An avid wine lover, the

communist leader got sick with diabetes in his final years. One vineyard in Huși, eastern Romania, came up with a solution to allow the

dictator to relish a glass of wine.

Everyone

knew what was Nicolae Ceaușescu’s

favorite wine, zghihara de Huși, a grape

varietal that amassed very little residual sugar and a higher acidity rate.

Hence the wine was ideal as an appetizer, since that acidity stimulated the

gastric acid that helped the digestion process. This type of wine made Ceaușescu adopt him, under the council of his doctors, who

told him this wine had a low sugar concentration and wouldn’t

hurt his diabetes. Thus hundreds of bottles would be sent to the Central

Committee and it was hence known as Ceaușescu’s wine. Elena Ceaușescu, on the other hand, would also drink Cabernet

Sauvignion, she particularly enjoyed wines from Dealul Bujorului. The wine had

to be semi-dry, with residual sugar that left a sweet taste at the end. Funds

were invested to plant 40 hectares of zghihară in Huși. The original vineyard had a smaller surface, so the money from the

Central Committee helped popularize this particular varietal and increase its

production. In every cocktail party Ceaușescu organized, he would serve his

wine and, whether they liked it or not, people would smile and always praise

its merits because it was the polite thing to do.

The

history of Romanian wine after World War II also includes a number of social

elements that affected the production of this elixir of life. And its history

is bound to extend many years in the future as well. (VP)