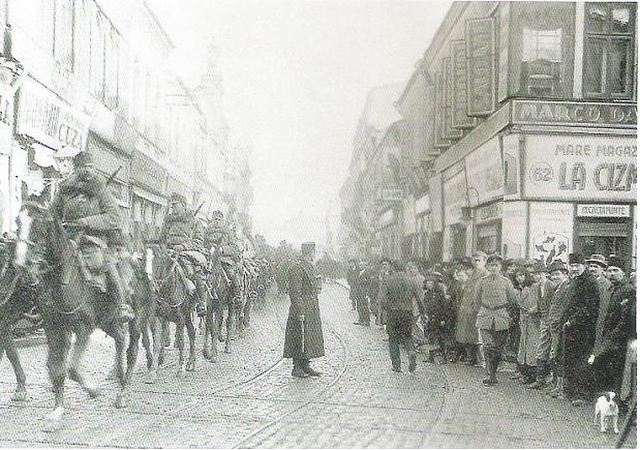

Romania took sides with the French-Anglo-Russian

alliance in August 1916 and formally entered World War One. In the wake of

nearly four months of violent fight, on December 6, 1916, the German army

occupied Bucharest. The Romanian authorities fled the capital city withdrawing

to Moldavia, in the north, but their withdrawal was simply chaotic. All

throughout that chaotic period of time, in the last night of 1916, nearby Iasi,

the most serious railway accident in Romanian history happened. About 1,000

people lost their lives as an oversized and overloaded train derailed in the

locality of Ciurea.

The historian Dorin Stanescu specializes in the

history of Romanian railways. He made an in-depth research of the great

accident. According to Dorin Stanescu, along a railway network of 1,330

kilometers in Moldavia, 1,000 locomotives and roughly 25,000 railroad carriages were

pulled over, that is Romania’s entire railway fleet, which literally blocked the

railroad lines, while the rolling of trains became very difficult.

Dorin Stanescu:

As the Romanian army was withdrawing to

Moldavia, a train was departing from Galati on December 30, 1916, at a time

when the city of Galati was under the German bomb-shelling and the German

occupation of the city could hardly be avoided. The train was overloaded,

heading for Iasi. There was a couple of hours’ delay in the scheduled departure

of the train. It was an overcrowded train, since many civilians wanted to go to Iasi.

Joining them were GIs who were on leave and obviously had to return to their

military units, there were also several Russian soldiers on board the train. We

must say that among those who boarded that train there were such personalities

as that of former finance minister Emil Costinescu, then there was the daughter

of former French ambassador to Bucharest, Yvonne Blondel as well as the geographer

George Valsan.

Dorin Stanescu:

The train became overcrowded as

other carriages were added along the route, while people were literally storming

those carriages. Very many people opted for boarding the train at all costs,

using event the rooftops of the carriages. So from one railway station to the

next the train was getting longer and got more and more crowded. Now, if we

think of the size of the carriages that were rolling at that time and their

available space and if we check the number of passengers as against the

available compartments, the buffers-and-chain coupling system of the carriages

and the rooftops, and examining the accounts as regards the number of carriages,

we may find out that no less than 5,000 people were on board the train, whereas

the train had a seating capacity for no more than 1,000 people. Everybody was desperate

to flee Galati, while the GIs were desperate to make it to their military

units.

On December 31, 1916, the train departing from Galati

and having Iasi as its destination point was reaching its final leg. But this

final part of the journey would be a tragical one.

Dorin Stanescu:

On December 31, 1916, the train

reached the town of Barlad and was stationed there during the night of December

30 to December 31. The following day the train rolled on, there were 120

kilometers to roll before reaching Iasi. The train hit the railway station of

Ciurea at about 12 am, the locality and the railway station were just a couple

of kilometers away from the city which was lying along a valley. It was a harsh

winter and the snowfalls had been abundant. When the train began rolling

downward along the slope, the mechanics activated the brake system.

Unfortunately, the train was so crowded that the people who were responsible

for that could not activate the proper mechanism of the carriages which had

hand brakes that were manually operated for each carriage, so that the train could

be slowed down. The train was rolling at high speed and ran off its rails.

In the railway station of Ciurea, all the rails were

full of passenger carriages and cistern tanks with a liquid cargo of oil. When

the train ran off its rails it bumped into other carriages which caused a terrible deflagration. According to eyewitness accounts, the explosions were quite like

a small-scale earthquake. Many people were thrown off in the snow but many more

died because they were crushed between the carriages, while others got killed

in the explosions. Estimates of that time reported as many as 1,000 deaths.

The aftermath of the terrible accident was

predictable, and the survivors and their descendants claimed justice.

Dorin

Stanescu:

Quite a few of the victims or their successors tried to file lawsuits

against the Railway Company and the Romanian army to receive compensations. The

case stalled, obviously, and the legal conclusion was that the territory was

under the jurisdiction of the army and the damage fell under the category of

war damage. Oftentimes the dead person takes all the blame, in Romanian

society. All the inquiry committee chose to say was that, because of the people

on board who blocked the maneuvers the personnel was supposed to make, the

train could not be stopped. There is a similarity with another accident that

happened in a similar context, this time in France. On December 12, 1917, in

the region of Savoy, a train loaded with French soldiers who were on leave, as it was

rolling along a hill, ran off its rails; the aftermath of that accident was

about the same, and so were the conclusions of the inquiry. Nobody was held

accountable for that tragedy. That train was also overcrowded and 400 people

died. Scapegoat hunt back then was purposefully avoided, and it was the war

that pleaded guilty.

The accident in Ciurea, on the New Year’s Eve of 1917,

was quite uncommon at that time. However, the war itself is something which is

quite uncommon.

(Translation by Eugen Nasta)