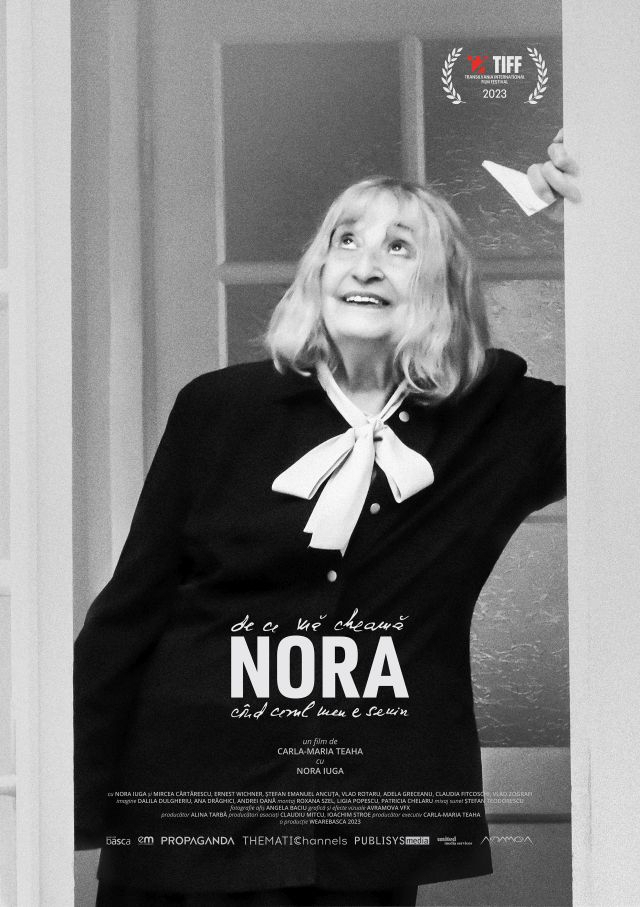

One of the most successful Romanian films last year

was Nora, written and directed by Carla-Maria Teaha. The first foray into

documentary film-making from Teaha, who has previously worked as an actor and

radio journalist, the film follows Nora Iuga, one of the most important writers

in this country, who turned 93 years old on 4th January. Released in

2023 at the Transylvania International Film Festival and also screened at

Anonimul and Astra Film Festival, Nora creates a touching portrait of

this charismatic writer and poet who made her debut in 1968 with a

book of poems (Vina nu e a mea), received a number of awards from the Writers’

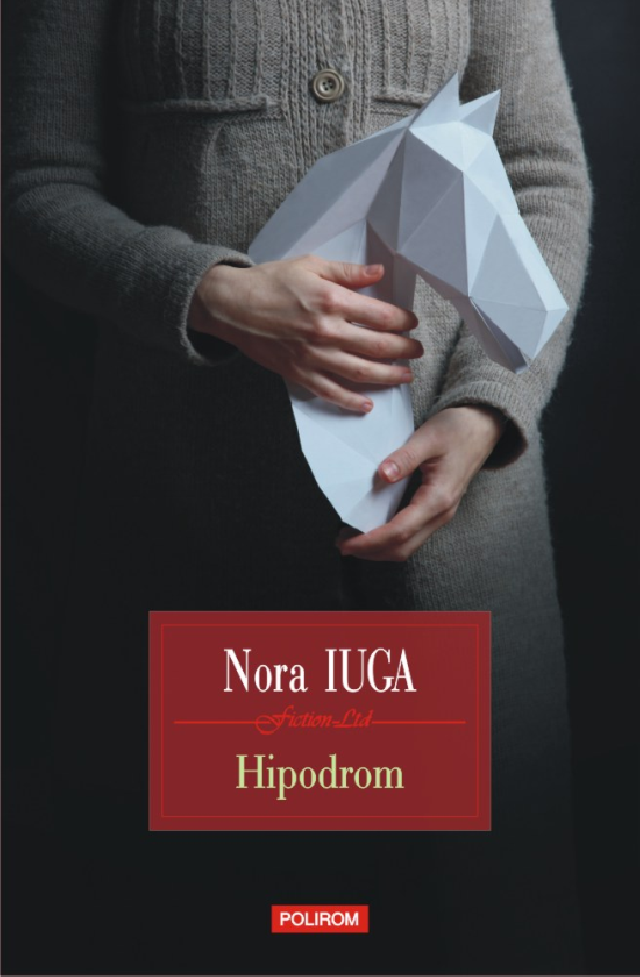

Union and has remained very active, publishing an autobiographical

novel (Hipodrom) in 2020 and another book of poems in 2023 (Fetiţa strigă-n

pahar, Nemira).

Shot over the course of four years, the film also

captures Nora Iuga’s fascinating inner life as she has retained her

youth and contagious exuberance, as well as the special friendship

between her and the director, who accompanies Iuga at the Frankfurt

Book Fair. We spoke to Carla-Maria Teaha about how she created

the documentary film and the enthusiastic response of the public:

I didn’t have a certain script in

mind, especially for our trip to Frankfurt. From the very beginning I

wanted the dialogue to be created by speaking freely with Nora. Starting

from what would appear to be mere chit-chat, my intention was

to get Nora Iuga to tell her stories, because along with other qualities,

she is a fascinating story-teller and the camera loves her. This is why I never

felt the need to introduce other characters that would speak about her. As this

is my first film and I didn’t have a lot of experience in this area, I relied a

lot on my intuition and I wanted to show Nora Iuga as I see her. I decided I

wanted it to be a film about this Nora Iuga even if I would fail, so I based it

on the chemistry between us and the things that I find touching about her. And

what’s fascinating is that people were able to relate to me, to this image I

had of her. Deep down I hoped this would happen, I hoped Nora Iuga’s charm

would have the same effect on the public that she had on me. Moreover, I worked

very hard on this film. I was brimming with joy at the reaction of the

audience, when, at TIFF, the film received standing ovations after the first

screening, on June 14 last year. People also stayed for the Q&A session,

nobody left. And somehow that very strong impact the film had on the audience

did not diminish at all, after the screening in theatres people stay in there a

little longer and applaud, even though we’re not speaking about a special event

and we are not there with them to have discussions. I am very happy because of that, I am happy

because film had such an impact and because it has done its job, I am happy it

touches people. I really thought it was just as normal for Nora Iuga’s fans to

be keen on watching the film, but I am also glad that even those who didn’t

know her or were unfamiliar with her work, fell in love with her. So many

people told me that, having watched the documentary, they bought her books,

searched for interviews with her, they were even looking for info about her. It

is wonderful that, through this film, we succeeded to bring fil aficionados and

reader together, these two bubbles somehow met, which is great, I think.

Before becoming a writer, Nora Iuga wanted to become

an actress, so the documentary made by Carla Maria-Teaha made Nora Iuga’s dream

come true.

To tell you the truth, I wanted

to become an actress ever since I was in high-school. I ‘ve always wanted to

become an actress, perhaps it is something that comes from my family, my

parents were artists and so were my grandparents. My mother was a ballerina,

father, a violinist, one of the grannies was an opera singer, a grandparent was

a stage director, so I never thought of myself as taking a career path which

was different from that of an actress. I have always dreamed of that, what’s

most astonishing is the fact that I have never ceased to want to become an

actress, even after the great actor Radu Beligan flunked me at the Drama School

admission exam, telling me my elocution was not good enough. I personally do

not think there is a problem with my elocution, other people didn’t tell me

that either, yet I cannot question Radu Beligan either. Now, returning to the film

made by Carla Maria Teaha, as days go by, it comes as something clearer and

clearer to me that it was all about a miracle, a very old dream of mine came

true just now, after a lifetime.

Mircea Cărtărescu heaped praise on Nora Iuga’s most

recent poetry volume. Fetita striga-n pahar is hitherto the peak

of Nora Iuga’s poetry and one of the most powerful poetry books I have read

recently. It is like a shrapnel exploding in your face, spreading splinters,

shards, rough pieces of metal, of memory, of brain, of quotes, of any kind of

stuff suitable to write on your skin the judgement of a fragmented, abused

beauty .