The one-week “ski holiday”, as it is usually known, is scheduled in Romania in February. It is part of the secondary-school timetable. Also, its timeframe is subject to change, according to decisions taken by local municipalities.

In Oradea, in the northwest, the Oradea Cris Rivers Museum – Museum Compound jointly with Bihor County Council and the Municipality of Oradea staged an activity themed “ With grandparents at the museum. Guides for one day “. During the February 18th and 23rd school holiday, grandparents and their grandchildren are invited to get acquainted with the history of the town. Accordingly, grandparents will have the opportunity to act as guides, for the grandchildren.

Cristina Liana Pușcaș holds a Doctor’s degree in history. She is a museographer with the Oradea Town Museum, a section of the Oradea Cris Rivers Museum. Dr Puscas told us more about the project.

“Practically, it is the 2nd edition of this program which we initially thought out in 2023. The following year, in 2024, we could not stage it since the museum underwent a thoroughgoing refurbishment process. We thought out the project to be implemented throughout the ski holiday, bearing in mind not all the children could afford going on such a trip, so quite a few of them stayed at home, in their hometowns, in Oradea, mostly, with their grandparents, who could afford going out for the day, in a bid to get acquainted with the history of the town, at once sharing their own life experience with their grandchildren.

Last year, through this large-scale project of refurbishing the Town Museum section, we arranged a couple of museum areas, new exhibitions, quite a few of them dedicated to that specific period of communism, an era those grandparents used to live in, so their own life experience can be transposed into stories, in each of the dedicated rooms. “

Dr Puscas told us more about the project.

“They can, for instance, speak to the children about the significance of the fish placed on top of the TV set, about what those bottles of milk meant, how they were queuing up, the soda bottle, the petrol lamp reminding everyone of the fact that at that time, in the evening, they had power outages for a couple of hours, about the dial telephone.

As part of the exhibition themed “Education in Oradea in the 20th century” we have a classroom of that time, with the school uniforms, with the pioneer’s uniform, we have the ink glass, the letter box, the abacuses, so much so that the stories and the life experience of those grandparents can be explained much easier. Another exhibition children may find extremely attractive is the one themed “The Discotheque of the 70s and the 80s”, since grandparents lived at that time, so they can spin the yarn of what life meant, at that time, for them, when they were young. “

The museum staff also prepared additional info for the halls in the museum that were a little bit more difficult to explain by the grandparents turned guides, our interlocutor also said.

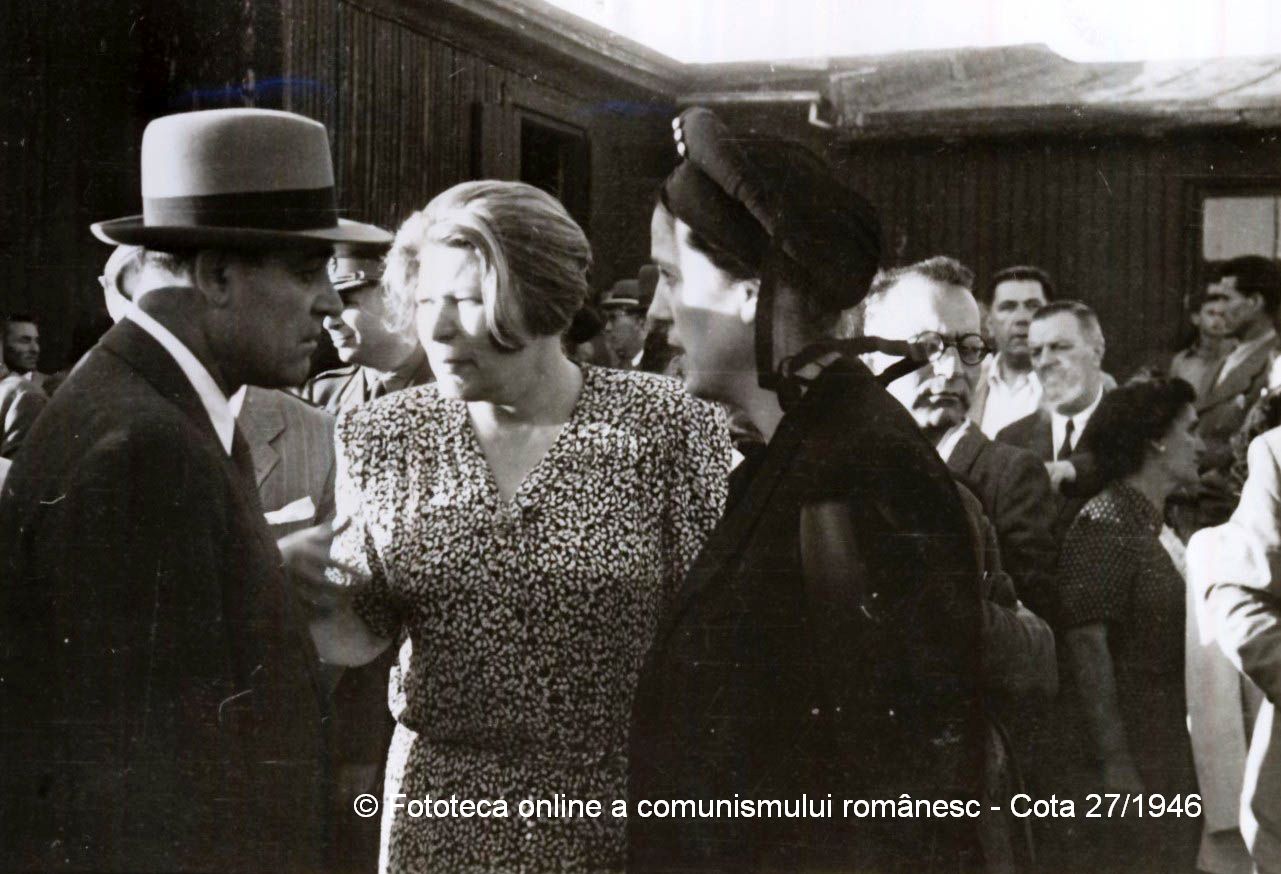

“It goes without saying they cannot possible have such comprehensive notions, For instance, for World War One, we have prepared a brief piece of info on what the Romanian Army’s entering Oradea in 1919 actually meant, to be more specific, who Traian Mosoiu was, the hero who contributed to the liberation of the town. And speaking about the day-to-day life, in the communist times, we also have a flyer with info and images that can, in effect, trigger grandparents’ memories of what the communist times meant. “

We asked Cristina Liana Pușcaș what the successful points were, of the 2023 edition of the project:

“Taking a quick look at the photos of two years ago, I realized grandparents really came, with their grandchildren, and they were having a closer look at those objects. And from the photos, you could see them explaining how the telephone worked, for instance, with a dial, how a radio worked, how a turntable worked, for instance, what the vinyl was good for and from those photographs I even recalled grandparents truly got involved in the description of quite a few of those objects.

As we speak, exhibitions are pretty well stocked with such objects, so grandparents will definitely have much more pieces of info at their fingertips, enabling them to give much more detailed explanations to their grandchildren. “

The entrance fee for one ticket as part of this museum program is 10 lei per person, that is 2 Euros, for the master exhibitions of the Oradea Town Museum Section. The Oradea Museum Town Cultural Complex, based in the Oradea Fortress makes temporary and permanent exhibitions available for visitors.

Here are some of the themes of the museum’s permanent exhibitions: ”Churches in the palace – archaeological research in the Princely Palace”. “The History of Bread” The History of Oradea Photography”, “The Convenience Store”, “Childhood in the Golden Age. The Resistance and repression in Bihor Memorial”. Then there is the “Moving Monuments Exhibition. Depersonalisation”, of fine artist Cătălin Bădărău. There are also The Oradea Greek-Catholic Bishopric Exhibition – Pages of History, the Exhibition of the Oradea Reformed Church and the Oradea Roman-Catholic Bishopric Exhibition.