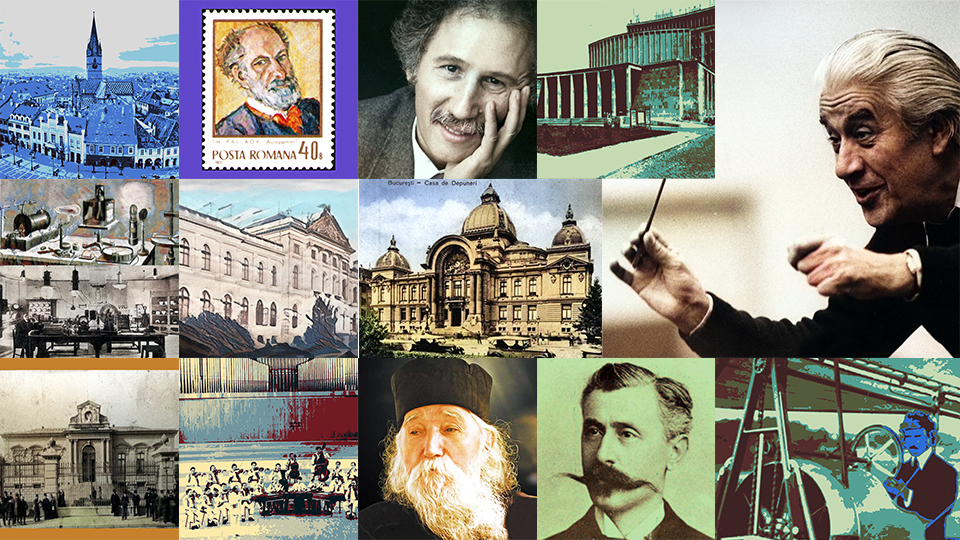

The literary society “Junimea”, founded in Iași in 1863, was one of the most important literary, philosophical and political trends in Romania. And one of its five founding members was Titu Maiorescu, a lawyer, literary critic, writer, journalist, aesthetician and politician. He also left his mark on the career of Mihai Eminescu, considered by many to be the greatest Romanian poet.

With his full name Titus Liviu Maiorescu, he was born in 1840 in Craiova, and died in 1917 in Bucharest, at the age of 77. His father, Ioan Maiorescu, a professor, diplomat and author of history books, was an active participant in the 1848 revolution in Wallachia and Transylvania. Titu Maiorescu studied law, literature and philosophy in Vienna, Berlin, Giessen, and the Sorbonne. Even during his high school studies, he stood out for his ambition and tenacity, graduating from the Theresian Academy in 1858 at the head of his class.

His intellectual career began at the age of 17 when he tried to publish literary translations in “Gazeta de Transilvania”, the most influential Romanian-language newspaper in the Habsburg area. After graduation, he taught psychology and French. In 1861, he published the first philosophy text in German, influenced by the post-Kantian realism of Johann Friedrich Herbart and the Hegelianism of Ludwig Feuerbach. In his prodigious work as an author, Maiorescu wrote several dozen volumes of literary criticism, philosophy, aesthetics, logic, history, parliamentary speeches, and his diary is a creation that includes over 10 volumes and is considered the longest diary in the history of Romanian literature. On a personal level, in 1862 he married his student, Klara Kremnitz, to whom he had taught French language courses and with whom he would have a daughter.

In 1862, returning to Romania, he was appointed prosecutor at the Ilfov court, and became a professor at the University of Iași where he taught the history of Romanians. At the same time, he also taught Romanian language, Romanian grammar, pedagogy, and psychology at high school level. He spoke at public conferences on topics and subjects of law, literature, history and pedagogy. Maiorescu’s presence and competence in so many fields may seem excessive today, but the times demanded involvement. It was a period in which Romanian intellectuals were in the midst of the process of reforming the state and reinventing society according to the Western model. At the same time, they were trying to integrate new ideas and models that were appearing in the West. Literary historian Ion Bogdan Lefter noted Titu Maiorescu’s involvement in that considerable effort, an effort that had to be made by a thin layer of elites, and which was not only an effort in a single field of expertise.

“Everything had to be founded, from scratch, including discursiveness, which is why Maiorescu makes personal efforts. In the meantime, he practices daily in diaries, but as a public discourse he writes one text at a time, after a while another text, watching what happens. At the same time, he witnesses, with exceptional intuition, the way in which what accumulates, and the way in which what accumulates will one day manifest. For example, the end of his preface, a famous one in the Eminescu edition, which he himself drafted against the author’s will, shows us a visionary through this text as well. He uses formulations of looking towards the future. He says ‘as far as humanly possible to foresee’, and what did this mean? It meant that Maiorescu and his group understood the extraordinary value of Eiminescu’s poetry. They read and understood both Creangă and Caragiale, they understood the phenomenon, they saw the direction, but the ensemble could, at that moment, barely foresee it, it did not yet exist. It would consist of pieces not yet assembled into a whole.”

Although he had certain competences in several fields, Maiorescu felt closer to literary criticism. Ion Bogdan Lefter noted Maiorescu’s efforts in the field of literary criticism, part of the world of ideas at that time.

“Maiorescu has a very broad, comprehensive, civilizational understanding, at a time when the accumulation of literary raw materials was still precarious. He is the one who assists and, in a way, stimulates the appearance of the first literary works of the highest level at Junimea, with all its story and the extraordinary group of which he was part of. His contributions are written, they are in the few fundamental texts, they are essential. He himself is a first literary critic, if we can truly call him a literary critic, considered the founder of literary criticism, with equally important contributions in the founding or structuring, crystallization of other socio-human disciplines in Romania.”

Titu Maiorescu was also a politician. He was close to the values of the Conservative Party, but in the governments of this party he represented the Junimist group, a liberal-conservative group. Starting with 1871 he held parliamentary deputy terms, and served as Minister of Education. Between 1912 and 1913 he was Prime Minister, and signed the Peace of Bucharest after the Second Balkan War, when Romania obtained Southern Dobrudja. In 1914, on the eve of the outbreak of World War I, and 3 years before his death, Titu Maiorescu retired from politics.