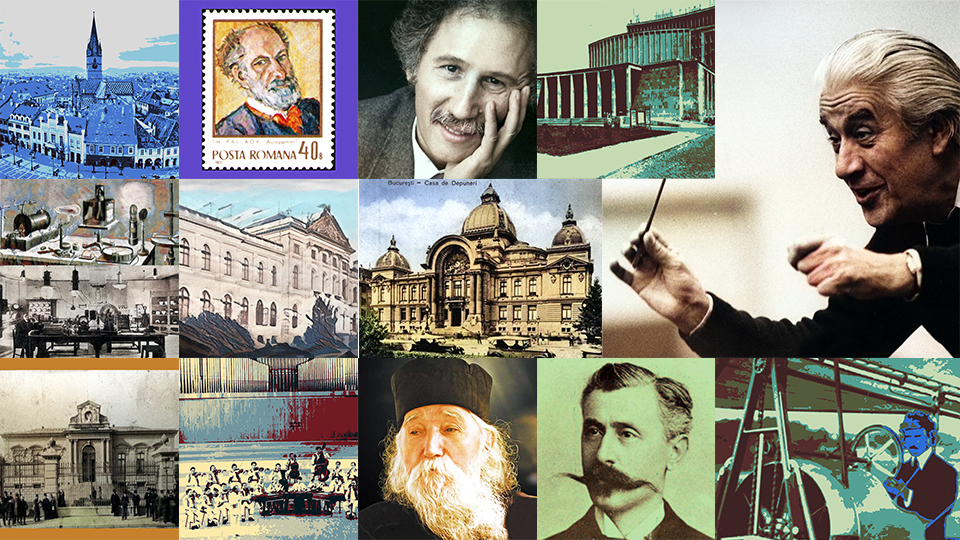

Sighișoara is one of the cities in Romania that has preserved an appealing medieval center. The name of the famous prince Vlad “Dracula” Țepeș, born here in 1431, a medieval art festival, the fortified citadel, the Clock Tower and several other points of attraction are tied to the city. There is also a museum in Sighișoara which in 2024 will celebrate 125 years of existence.

Today, Sighișoara is located where the Roman military settlement Sandava once stood. The city was founded later by German settlers from Franconia, deployed by the Hungarian king Géza II in the 12th century. The first documented records of the city, however, date from the late 13th century. In its 800 years of existence, Sighișoara went through periods of peace, but also through moments of fear and violence such as invasions, peasant uprisings, wars, sieges, plague epidemics, fires or social unrest. Sighișoara’s millennia-old history can be examined today at the local museum. Its director, Nicolae Teșculă, outlined some chronological milestones of the museum since its establishment.

“The 19th century is particularly known as a century of nationalism, of nation-making, and of course, every nationality wanted to preserve and express its national values. This should also be produced through the creation of museums, by preserving some artifacts that identify a nation with a certain territory”.

After the establishment of the Brukenthal Museum in Sibiu in 1817, local collectors made efforts to create new museums, such as the one in Sighișoara. Nicolae Teșculă gave us more details.

“First of all, we’re talking about the collection of the German high school. The teaching staff of the Evangelical High School collected objects for school use. On the other hand, in 1879 Sighișoara hosted two events. The first was in early July, a general meeting of the Transylvanian Association for the Culture and Literature of the Romanian People, later known as ASTRA. Also that year, there was also a meeting of the Historical Science Society from the eastern part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. One of the initiators of the organization of this session was theologian and historian Carl Fabrițius, originally from Sighișoara and a teacher at the German high school. On this occasion, he collected several objects from Sighișoara and the surrounding areas and set up an exhibition. This somehow served as his legacy to the younger generations to organize a museum in Sighișoara in the future, considering the exceptional value of the citadel that preserved and still preserves these medieval values”.

The joint efforts of the Sighișoara elites in storing and exhibiting objects that remind us of the past were highly successful. Fabrițius was the one who started the history of the museum and his effort would be continued by Josef Bacon. Nicolae Teșculă explains.

“One of the volunteers who contributed to the exhibition was a young man at the time, Josef Bacon. Later, he studied medicine and returned to his hometown, becoming the city physician. At the end of the 19th century, a museum would be set up in the most representative tower of the fortress, the Clock Tower. Initially, this tower had been restored in 1894. Later, it seems that a small exhibition, the so-called patrician room, was organized on the ground floor of the Clock Tower in 1898, although there is not much available data on it”.

All good things usually progress and end well, and the same is true of the museum in Sighișoara. Nicolae Teșculă.

“Later, more objects were added to the collection, basically, on June 25, 1899, the museum opened. It brought together a group of generous and history-loving people, and from 1905 it was linked to the Sibiu-based Sebastian Han Association. This association was specifically aimed at promoting historical and artistic values. It had two goals: on the one hand, the organization of exhibitions in different fortresses or fortified churches and, at the same time, the promotion of visual artists from the area, especially Saxons, who at that time were active in the centers of Transylvania, especially in Brașov and Sibiu. This Association administered the museum until 1925. After 1925, the museum came under the tutelage of the Evangelical Church, which started expanding its collections. In addition to the Clock Tower collection, which included the early history of Sighișoara, starting with the Bronze Age and ending with the First World War, there was also a small ethnographic museum set up in the monastery church, a small museum of church objects organized in the hill church and a school museum. They even tried to create a small dendrological park around the Clock Tower and the green area between the church and the tower, and starting 1933 Sighișoara has arguably had a genuine museum complex”.

The history museum in Sighișoara is today one with a century-old tradition, built with the enthusiasm, dedication and experience of a group of people who more often than not remain unknown to future generations. (VP)