Romania and North Korea had a very close relationship, which began in the 1970s. The two leaders, Nicolae Ceausescu and Kim Ir Sen, paid visits to each other, liked each other, trying to boost bilateral relations and bring their countries closer. A very rigid interpretation of the Marxist-Leninist ideology and the wish to emancipate from under the Soviet and Chinese influence, respectively, were the core elements of this relation. Consequently, Romania and North Korea found ways of dialogue and cooperation.

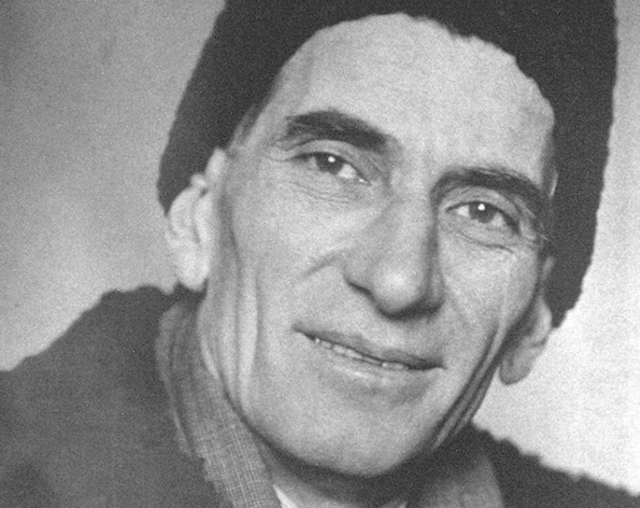

In 1970, Colonel Emil Burghelea was designated military attaché to Pyongyang. In an interview to the Oral History Centre of the Romanian Radio Broadcasting Corporation in 2000, he explained the context in which he was appointed military attaché although he didnt speak Korean and was not prepared at all to hold that post.

Emil Burghelea: The main arguments I was given were that as an officer I could easily adjust to any conditions, and that I was fluent in Russian, a language spoken by many Koreans. Furthermore, there were Koreans who spoke Romanian, too. So, all conditions were met for me to accomplish my tasks in Korea. During the Korean War, several thousand children from Korea came to Prahova Valley, in Romania. They learnt Romanian very well, as children are fast learners. Children of military attaches lived in hostels here, and then returned to Korea, all of them having a very good command of the Romanian language. Here is a joke: during one of the Romanian governmental and military visits, the delegation led by Emil Bodnaras was received ceremoniously by the Korean state and party leaders. Bodnaras was offered very good accommodation. He was an officer by profession, just like me, and a former illegalist, well aware of what life in the army and banned political parties involved. He was accompanied by a Romanian language interpreter. He told us that he wanted to know how many Koreans were speaking Romanian, and on a free day, while enjoying a moment of relaxation, Bodnaras had the idea of telling a rather dirty joke. I remember Bodnaras telling us the interpreter didnt even start to translate it that 10 people burst into laughter. How well did they speak Romanian? Well, they were speaking a broken language. For instance, they were using the phrase “fatherly father. I told them a father is a father. Whats that fatherly father? Later on, I understood they were trying to avoid confusion with Koreas leader, who was referred to as the father of the nation.

Meanwhile, relations between Romania and North Korea got tighter and tighter, even privileged, according to Col. Emil Burghelea:

Emil Burghelea: “The relations between our countries were excellent, because the leaders of the state and party had close relations, and I myself had a privileged status as a military attaché in North Korea. I had access where no other military attaché had, not even the Russian or the Chinese ones. They had a reserved attitude towards the great powers, even if two million Chinese had died in the Korean War. There were lots of exchanges and delegations, including in the field of weapons trade, and usually the co-chair of the delegation or government commission was the controversial General Vasile Ionel. There was also a joint economic commission, there were many such organizations designed to strengthen collaboration in all areas.

Romania was exporting large amounts of trucks, cars, machine tools and industrial products to Korea:

Emil Burghelea: “Every single request I made was met, even the personal ones. I had some trouble with one of the kids that was back in Romania, and it got to the point where a minister gave up his seat in an airplane for my wife to be able to go back home and take care of him. I was not the type to make too many requests, but that was a serious situation. They would answer right away, I had access to places where no one else had, from their underground weapons factories to their fortifications on the DMZ. They were running around desperately trying to build a weapons industry for themselves. They worked in medieval conditions, but they were turning out weapons. I mean the conditions were very, very difficult, like the Middle Ages, when they made cannons out of cherry tree trunks. They made special steel for cannons, and you couldnt but be amazed at how they managed to pull that off. Back in Romania, we were always told to go to the West to get information, with lots of money spent for this purpose. One other thing was that of mobilizing Koreans, caught as they were between four great powers, Russia, China, Japan and the US. We were giving them automated lathes built at Arad and Brasov. And we found out that they would remove the labels saying Made in Romania, put labels in Korean on them, then sent them to South Korea and claimed they were manufactured by them. We knew what they were doing, but we didnt say anything. They stole from others too, not just from us.

The Romanian-North Korean friendship reached legendary proportions. Some historians say that Ceausescu was strongly influenced by North Korea. After 1989, relations between the two countries were substantially re-evaluated.