He established a significant presence for himself in intellectual and student circles. He was a second child to a family with a Ukrainian name, changed later into the Romanian ‘Porumbescu’. Adina Istrate, a museographer with the Ciprian Porumbescu Memorial House in Stupca, told us about the composer.

Adina Istrate: “Ciprian Porumbescu inherited his patriotism from his father, who was a priest, as well as a patriot, folklore collector and 1848 revolutionary. Ciprian studied music with Karol Mikuli, a former student of Chopin and later director of the Conservatory in Lemberg, today’s Lvov. Ciprian studied piano with him for six years, before playing in the troupe of great traditional musician Grigore Vindereu.”

Passionate about the emancipation of Romanians in Bukovina, back then an Austro-Hungarian province, Ciprian Porumbescu went to Putna on 15 August 1871. Putna, the monastery where Stephen the Great is buried, hosted that day a congress for Romanian students across the world, held by the ‘Young Romania’ Society. It was organized under the leadership of famous Romanian writers Ioan Slavici and Mihai Eminescu. This was the first time that Ciprian Porumbescu met the greatest Romanian poet. Two years later he went to Chernowitz to study philosophy and theology. There he became the president of the ‘Arboroasa’ Society, an association of Romanian students from Bukovina, which organized actions considered hostile towards the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Adina Istrate: “It all culminated in a condolence telegram sent in 1877 to Iasi City Hall on the 100th commemoration of the decapitation of ruler Grigore Ghica III. That telegram was signed ‘Youth from the cut off part of old Moldavia’. It was the expression ‘cut off’ that bothered the Austrian authorities, who held in detention all five members of the Arboroasa Society Committee for 11 weeks. Unfortunately, Ciprian fell ill in prison, catching the TB that would lead to his death. However, the trial resulted in the release of the five, who were found not guilty.”

Between 1879 and 1881 he was in Vienna, where he continued his studies in music and philosophy. In the capital of the empire he met members of the Strauss family, and continued his patriotic militancy.

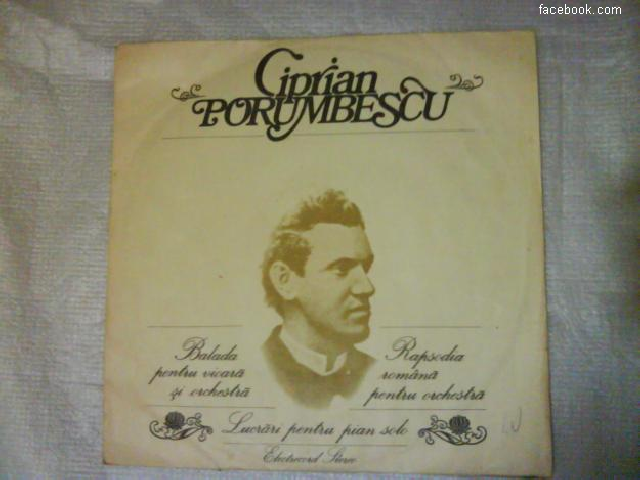

Adina Istrate: “He became a member of the ‘Young Romania’ Society and composed its anthem – ‘Union Is Written On Our Flag’ – a tune which is now the national anthem of Albania. Another song written by Ciprian Porumbescu was Romania’s national anthem before 1990. Also, while he was a student in Vienna, he printed a collection of patriotic songs for Romanian students. During the same period he composed his immortal ballad for violin, the best know and most beloved composition by Ciprian Porumbescu. After graduating in Vienna, he was given a teaching position at a school in Brasov, which he held between 1881 and 1882. This is the pinnacle of his career. It was the time when the first Romania operetta was staged, ‘Crai Nou’, on lyrics by Vasile Alecsandri. It was a very successful show.”

Unfortunately, his disease was progressing, and doctors sent him for treatment to a warmer area, in Italy.

Adina Istrate: “From November 1882 to February 1883, Ciprian Porumbescu went to Italy for treatment. He met Giuseppe Verdi there, and traveled to the major Italian cities of Rome, Venice, Pisa and Milan, and was impressed by their architecture. However, lacking money and missing home, he left Italy in 1883. He left behind 20 degrees Celsius for the minus 20 degrees Celsius of his home in Stupca, and this proved lethal. He died on June 6, at dawn, not even 30 years of age, after beseeching his sister to take care of his music.”

The people who love his music often visit his home in the village of Stupca, today renamed Ciprian Porumbescu, in Suceava county. This used to be the parochial house that the composer’s father, Iraclie, was granted when he came to the village as the local priest.