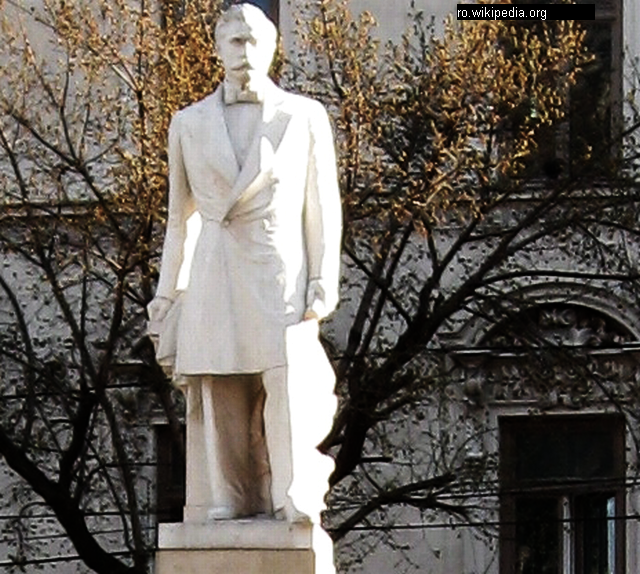

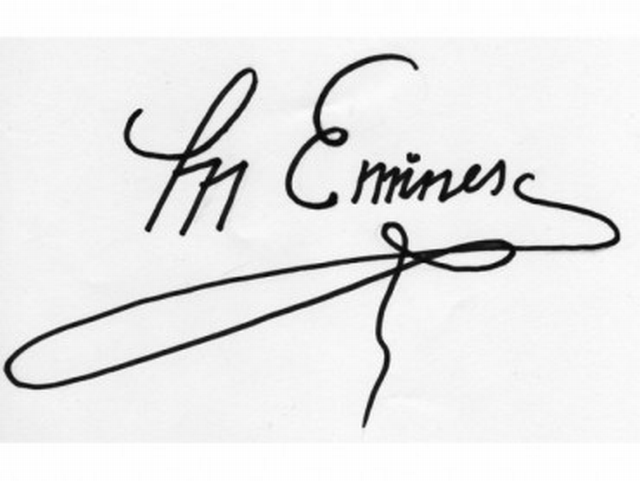

There are four statues in front of the University of Bucharest building in downtown Bucharest, one of them a bust of Spiru Haret. He was what we would call a polymath, having studied and excelled in math, physics and astronomy. He also reformed education. He was part of the generation of the first union of Romanians, that of 1859, when the medieval principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia united. It was also the first generation of people who committed to building a Western type democracy. Haret was an innovative spirit, a hard working person willing to put his efforts into building a dignified society.

He was born in 1851 in Iasi, at one point capital of the principality of Moldavia, part of the local Armenian community. He loved mathematics, and studied it to the fullest extent. As early as high school, Haret published two textbooks, one of algebra and another of trigonometry. In 1875 he got his degree in math in Paris, and the following year he got a degree in physics. In 1878 he earned his PhD in astronomy. In his thesis he continued research initiated by Laplace, Lagrange and Puisseux. His great contribution to the study of planets consisted in establishing that planetary axes are not absolute, as Kepler had postulated. In fact, Haret was the first Romanian to ever earn a high degree in that discipline. As such, there is a lunar crater named after him. When he became minister of education, Haret established the first astronomical observatory in Romania.

Even though he was invited to remain in France in a teaching position, he came back to his native Romania to fulfill a lifelong dream, that of reforming education. In order to do that, he realized he had to go into politics. He signed up with the National Liberal Party, and was appointed minister of religious denominations and education under several governments between 1897 and 1910.

His education reforms were not simply an effort to create institutions, it became an attitude in itself. The premise was simple. In 1899, Romania had a rural population of around 84%, with 87% illiteracy rate. The mathematician published a brochure called The Peasant Issue, where he was analyzing the state of retardation that Romanian culture was under, especially in the countryside. In his opinion, education reform had to occur at the same time that Romanian peasants were given land to own, alongside a reform of justice and administration across the board. This also had to be accompanied by the promotion of better labor values. The 1864 law of education introduced obligatory four year schooling for all, and was starting to show its limitations after 35 years. Haret realized that this system would doom the next generation to ignorance, putting in peril Romania’s economic future. Between 1901 and 1904, Haret introduced very effective reforms. One of his aims was to train people in trades that would result in the formation of a corps of public servants. He set up a large number of primary and lower schools, reduced high school to three years, and divided high school education in various specialty sections. He also did away with high school graduation exams, and established that university education was available only based on an entrance exam.

Haret was influenced by Auguste Comte’s school of thinking. He tried to use mathematical models in his social thinking, and started generating a model to explain social phenomena. In 1905, he published a book called Social Mechanism, where he stipulated that social balance may be obtained by the principle of minimal action. The direction was not very fruitful, since it was considered obsolete in Western academic circles.

Spiru Haret died on 17 December 1912, the same year that Romania incurred one of its heaviest losses, that of writer and journalist Ion Luca Caragiale.