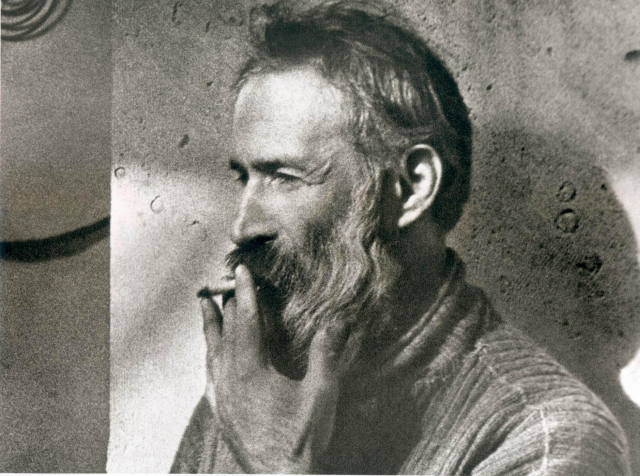

Carol I of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, the ruling prince of the United Romanian Principalities starting 1867 and the first king of Romania as of May 10, 1881, is still described as the most important state personality in Romanian history. During his 48-year reign, Romania gained its independence and became a constitutional monarchy: at that time, the foundation was also laid for the modern Romanian state. In terms of domestic policy, Carol I tried to strike a balance between various factors, favoring a climate of discipline and rigor, two qualities he acquired tanks to his Prussian-style upbringing, in a family with a strong dynastic tradition.

King Carol I gave his support for all economic structures to become modern, in a country whose political structures were still very much backward halfway through the 19th century. The capital city Bucharest itself resembled a country-side town. Yet Carol’s disciplined mind, a feature typical of all Germanic monarchs, as well as his experience as a King, were instrumental to speeding up Romania’s modernization. A politically astute personality, the King succeeded in having both liberal and conservative governments come to power, so that none of the two sides could have the possibility to undermine his authority.

Immediately after his arrival in the country, Carol I introduced an extremely important monetary reform, bringing the Leu on the money market. Although at that time it had not been an independent country, Romania managed to impose its own currency in 1867. Initially, only the metal coin was issued. Later, however, once Romania’s National Bank was founded, and also with the boost of private capital, in 1880 bank notes had also started being issued. With the help of the National Bank, but also through private capital, by early 20th century no less than 24 banks had been founded, while by 1914 an additional 210 were founded in Romania.

During the reign of Carol I, Romanian economy was predominantly agrarian. More than half of the peasants held plots of farmland with a surface area smaller than 5 hectares, while between 5 and 10 hectares of farmland were required for the support of one single family. It was a time of uncertainty for Romanian agriculture, so the so-called “people’s banks” were established. Such banks developed mainly because their managers were locals who were familiar with the circumstances of the local economy, and knew those who would take out loans. Most of the agricultural production was provided by the great landowners and for its most part was export-bound.

During the first forty years of Carol I’s reign, the country’s farming production grew six times. Agriculture provided a strong foundation for the entire economy, which had a strong bearing on Romanian industry. Crude oil extraction and refining saw a strong progress. Textile and foodstuff factories doubled their numbers. The influence of foreign capital on Romanian industry, however, led to the country’s industrial potential being clustered in certain regions, while other regions across the country were lagging behind. The Germans controlled 35% of the industry; following them were the British with 25%, the Dutch with 13%, the French with 10% and the Americans with 5.5%. The Romanian capital accounted for a meagre 5.5%. Between 1903 and 1914, most of the companies were founded, which later on would dominate Romania’s oil industry until the outset of the Second World War. Associate Professor Alin Ciupala, of the University of Bucharest’s History Faculty, has the details.

“During the reign of Carol I, Romanian economy remained an agrarian one, just as it used to be until 1866 and just as it would be in the interwar period. Yet a certain amount of change did occur. Late into the 19th century, a couple of resources were being put to good use, such as the crude oil deposits. For Romania, crude oil was an extraordinary opportunity and shortly afterwards the world’s biggest oil companies started doing business in Romania. Crude oil revitalized the country’s economy, since it was exploited by joint venture companies the Romanian state had set up with foreign companies. Profits, therefore, soon started coming in and the Romanian Government used the money primarily to develop infrastructure. Also, in 1887, the first important industry-boosting law was promulgated, aimed at stepping up the development of that sector of Romanian economy. However, as I said before, despite the fact that lots of new elements would appear until the First World War, Romanian economy was a predominantly agrarian one, and the main revenues were provided by the exploitation of the farmland. That also posed a big social problem, since the Romanian village was dominated by the existence of the large-scale land ownership. There were no small-time landowners, capable of representing the biggest part of land ownership, quite the contrary — in Romania there were big farmland estates, and that led to a rather low rate of agricultural progress. There was little to no interest in investing significant amounts of money in the development of agriculture, as long as big landowners were in need of cheap workforce.”

Quite unlike industrialized European states, urban areas could not absorb Romania’s large rural population given the country’s still weak industry. So strong was the mounting social pressure that in 1907 an unprecedented social movement broke out. The peasants’ uprising got the whole world witness the failures of King Carol I’st reign, within a year since the opening of the 1906 Jubilee Exhibition, which was meant to showcase Romania’s economic progress during King Carol I’s 40-year reign.