The belief in the involvement of terrorists and foreign secret services in the Romanian anti-communist revolution of December 1989 has become a national obsession that has dominated public perception of the most important event in the country’s recent history. The bloodshed in December 1989, the painful changes and the disappointment that followed have given rise to negative feelings about this event. We asked the historian Adrian Cioroianu from the Faculty of History of the Bucharest University who were these terrorists that everybody talked about in December 1989?

“At the time, we all believed terrorists were involved. They may have been mercenary troops from Arab countries or the so-called ‘Soviet tourists’. What we know with a certain degree of certainty today is that many of the people who fired guns in the few days before December 25th and sporadically even after this date could have been members of the Securitate, the secret police, who were still loyal to Nicolae Ceausescu. If we believe the conspiracy theory, we may speculate that it was all a big show to create the sensation of a revolution. It’s a theory I wouldn’t want to be true because it would mean that all those people were cynically sent to their death.”

People look at historians for a clear answer about the involvement of terrorists. The cautious explanations provided by the latter, are not, however, as convincing as the conspiracy theory. Adrian Cioroianu tells us about the difficulties facing historians in establishing what really happened:

“Until we have verifiable testimonies from the people who managed the situation at the time, historians will have a difficult task. We can but only record testimonies, but their credibility is questionable. People were in shock and there was a lot of chaos at the time, so it’s hard to distinguish between what is real and what is false. Historians, on the other hand, have to look for the truth. However, it’s almost impossible to arrive at the truth if the people who were in charge of the situation are not entirely truthful. The veterans of the intelligence services, who lost the war in December 1989, speak about a plot masterminded, according to some, by the Soviet Union itself. As long as we don’t have concrete evidence we can only speculate.”

The history of revolutions is full of counter-revolutionary elements opposing the revolutionary wave. However, the idea that terrorists were involved in the Romanian Revolution makes it an atypical event. Adrian Cioroianu does not agree:

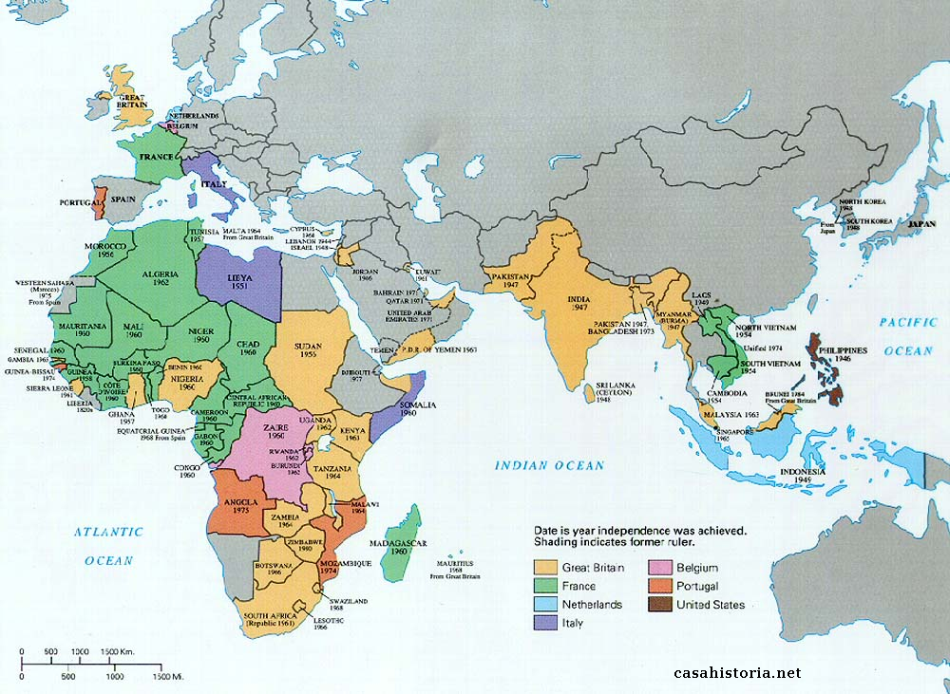

“I don’t believe the Romanian revolution is atypical. What’s certain is that it was different from what happened in other East European states, such as Czechoslovakia, Hungary and the German Democratic Republic. We must accept that the existence of a national-communist regime, something Hungary, Poland and Czechoslovakia did not have, predisposes us to believe that there were people who plotted against Ceausescu and people who defended Ceausescu. With hindsight, this polarisation and division into two conflicting groups is to be expected. Romania’s case is somewhat similar to what happened in former Yugoslavia, which also had a national-communist regime and where it took a long time to break with Miloshevich’s communist regime. National-communism has always created such problems and led to such internal conflicts.”

Is it possible that Romanians will once start having more positive feelings about the anti-communist revolution of 1989? Adrian Cioroianu believes they will:

“I’m convinced that more and more Romanians will reach the commonsensical conclusion that, at least in its extraordinary unleashing of energy, what happened in December 1989 can be described as a revolution. We have tried to refer to it in neutral terms as ‘the events of December 1989’ precisely because we want to avoid using a generic term. However, I believe we should call it ‘revolution’ because it had the consequences of a revolution, regardless of the goals of the forces who may or may not have masterminded the coup against Ceausescu. In the future, we may also be able to discuss about the involvement of our neighbours. Normally, in any situation of this kind, when events of such magnitude happen in a country, the secret services of the neighbouring countries will be on the alert. It is to be assumed that the secret services of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and Hungary paid close attention to what was going on in Romania. It was their duty to pay attention. Of course, it’s one thing to pay attention and an entirely different thing to become involved. It’s still not clear for us to what extent the Soviet Union was involved in the Romanian revolution. I’m convinced, however, that time heals all wounds, even in history.”

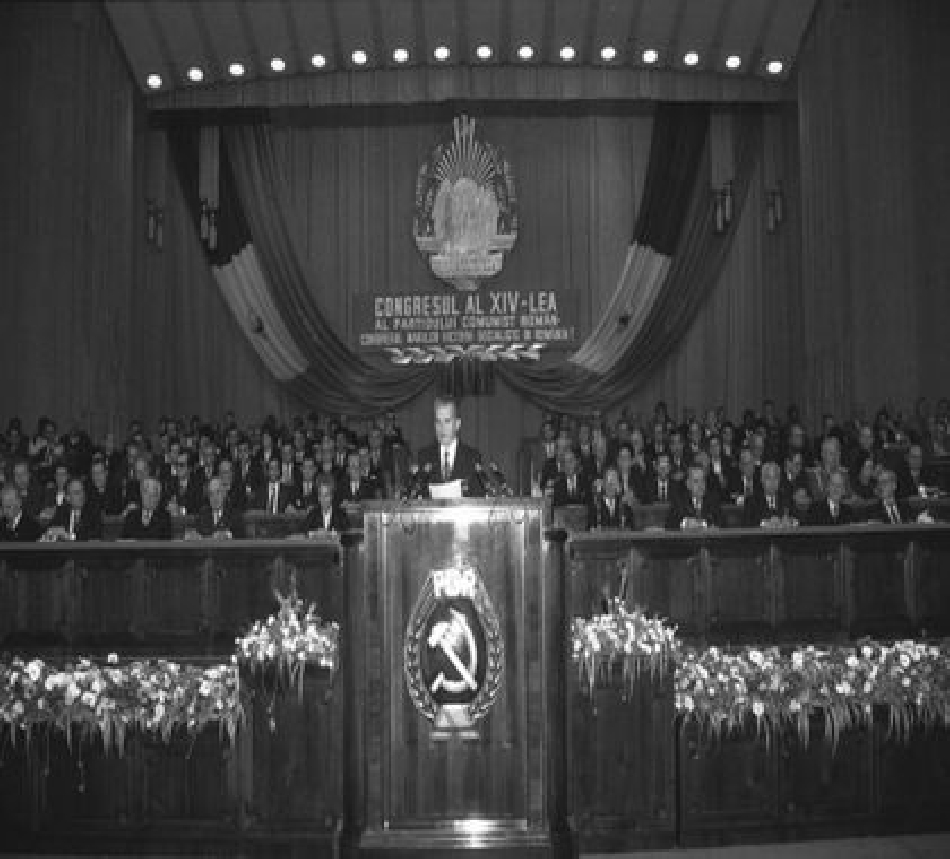

The Romanian revolution of December 1989 put an end to 45 years of communist dictatorship.