Rapid Bucharest is the oldest Romanian football First League club. Founded 100 years ago, in 1923, this is an immensely popular club in Romania, for a number of reasons: it is considered a workers club, it brought together fans of other clubs dismantled after 1945 by the newly instated communist regime, and was persecuted during Nicolae Ceaușescus regime, between 1965 and 1989. Rapid Bucharest won three national titles, 13 Romanian Cup titles and 4 Romanian Supercup titles; internationally, the clubs biggest achievements are a UEFA Cup quarter-final in the 2005-2006 season and two Balkan Cup titles.

In June 1923, the workers of the Atelierele Grivița factory eventually managed to convince the management of the Romanian Railways to fund a football team. According to the historian Pompiliu Constantin, the author of a book about the history of the club entitled “Rapid and rapidism” (Rapid și rapidismul), the club has in fact two birth dates: 11th and 25th June 1923. Supported by railway workers and the Giulești area of Bucharest, CFR Bucharest became by the mid-1930s a serious competitor for the strong teams Venus Bucharest and Ripensia Timișoara. Thats also when the club changed its name to Rapid Bucharest and its colours from purple to white and cherry red. The matches were played on ONEF stadium, later the Republic, and from 1936, on their own stadium, Giulești. In 1944, following political pressure from the communist party, Rapid went back to its original name as CFR, and later changed it to Locomotiva. It wasnt until 1958 that it went back to Rapid.

The club was popular for many years, being loved by many different generations of fans. Historian Pompiliu Constantin explains the reasons for this enduring popularity:

“In essence, this happened in the latter part of the 1930s, but especially after the dismantling of the inter-war clubs of Carmen, Macabi and Venus. Many of these clubs fans went to Rapid in the 1940s and 50s because it was one of the few clubs this surviving from the inter-war period. I even found articles about the estimated number of Rapid fans and it was clear it was the most popular club in the 1950s. It hadnt been the most popular in the inter-war years, Venus and Ripensia were more popular. The 1950s press estimated the number of Rapid fans at 1 million.”

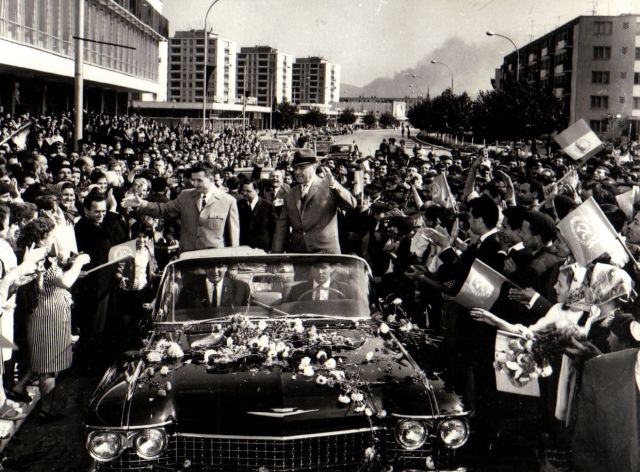

After 1945 and the installation of the communist regime, Rapid became one of the regimes favourites. Pompiliu Constantin explains:

“It was undoubtedly one of the favourites. Thats because the regime needed to promote the image of the team as one of workers who were also good athletes. From the documents Ive studied, Dej did not intervene, but Gheorghe Apostol, who was much more of a fan, tried to help the club in the 1950s when Rapid were demoted for the first time. Apostol, who was the leader of the workers in Romania at the time, sent a letter asking the Union for Physical Education and Sport, the leaders of Romanian sport, to agree that Rapid stay in the first league because they were the most popular team. His request was naturally rejected and Rapid were demoted to the second league, before joining the first league again.”