Nature is a fundamental presence in the existence of humankind. In effect, the human being cannot possibly exist without nature. Nature is the physical or the material world. In time, man explained the existence of nature as an irrational presence, but also as a rational one, the relationship the human being has with nature has always stimulated thought; one way or another, all ideas and branches of science are linked to nature. The modern world that began in the second half of the 18th century placed nature on a par with the divine, whereas the Middle Ages and the pre-modern era placed their stakes on the idea of the supernatural. Therefore, nature became part of political debates, so much so that conservative or groundbreaking ideas pay heed to its significance.

Nature as part of political debates would also emerge in the Romanian space. It was a French import. The Francophile Romanian intellectuals adopted the idea of nature, implemented it in politics, and analyzed its role and its relationship with politics in the set of attitudes man should have. Nature becomes essential in explaining the world from a political point of view.

Raluca Alexandrescu is a professor with The University of Bucharests Political Sciences Faculty. Dr Alexandrescu explained the source of the political debate on nature in the Romanian space.

We can already detect such tendencies in European logic, in the political discourse and in the European political narrative after 1850. An author I have already used as a landmark, precisely because, in very many respects, he is a source of inspiration and a role model, although I try not to use the world role model, is Jules Michelet. He himself has a radical change in discourse and in the research area of history and politics after 1851. “

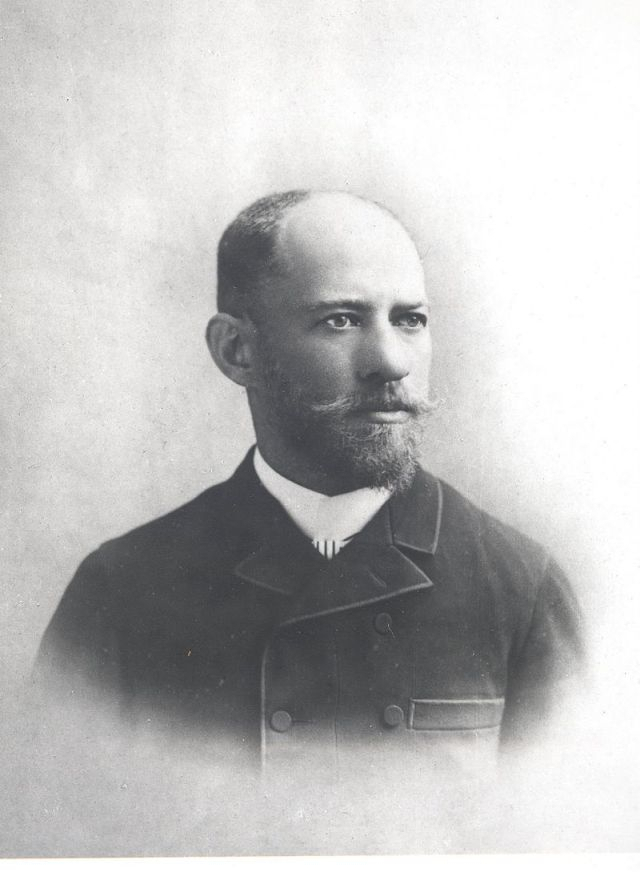

One of the first intellectuals who introduced nature in politics was engineer, geographer and writer Nestor Urechia. Raluca Alexandrescu has rediscovered his works and is now trying to put them into circulation once again.

Nestor Urechia was V. A. Urechias son. He is an author who, as far as I could infer talking to my fellow historians, political scientists or anthropologists, has enjoyed unprecedented attention, I daresay. He has been not studied very much so far, so he revealed quite a few of his many sides as a scientific personality. He is an engineer trained at the École Polytechnique și École nationale des ponts et chaussées from Paris, he is the main manager of the worksites building DN 1, National Road 1, which he supervised and built between 1902 and 1913, on the Comarnic- Predeal sector. At the same time, he is a vocal Francophile. His wife was French, in fact. He is passionate about mountains and nature. All these things coalesce to form a very stimulating set of reflections for the reader nowadays.

Urechia’s ideas stimulate the reader in reflecting on the relationship between territory, nature, democracy, sovereignty. This is an initial idea in Urechia’s writings that Raluca Alexandrescu wanted to remark upon:

“He observes that the earth is interesting mostly through its relationship with people. This is his main starting issue. The relationship with people did not just mean the aspects that we would see from an activist ecological perspective, meaning taking care of the environment, what we can do to protect it, but more than that. Urechia’s intent was to build a more theoretical proposal. His proposal took into account this more and more mobile, dynamic, more fluid relationship of society, of groups and individuals that compose it, with various forms of manifestation of nature, that form of cohabitation. This is interesting because this idea of peaceful cohabitation with nature, which today dominates the general discourse in general, is not very apparent in this period. Therefore, man and nature are actors with equal rights on a stage that brings them together under a harmonious political regime.

How does national belonging come about? Raluca Alexandrescu summarized Nestor Urechia’s answer:

“Another idea which is not so original, but is worth following in Urechia’s writing is the way in which he follows the construction of the modern expression of the nation in rhetoric about nature. Here we should rather refer to his novels, which are basically just stories. We are talking about a few volumes he published in early 20th century, such as Bucegi, The Spell of the Bucegi, and later The Robinsons of Bucegi. In these literary attempts we can see very clearly the intention to build the rhetoric of an identity, even a national one, relating to the way in which nature and politics blend together.

Today, nature and politics, just like 150 years ago, are present in what people believe is important for them and for the community they live in. Nestor Urechia is a name that Romanians can reflect on when they talk about themselves.(EN, CC)