Romania first

entered WWII in June 1941 alongside Nazi Germany, hoping to recover

territories it had lost to the USSR a year earlier. Three years

later, however, on 23rd August 1944, Romania broke off its

alliance with Germany and joined the coalition of the United Nations.

The immediate contact with the Soviet army was, however, brutal and

engendered a lot of negative sentiment in Romanian society for

generations to come. Radio Romania’s Oral History Centre contains

many testimonies about the abuse and violence committed by the

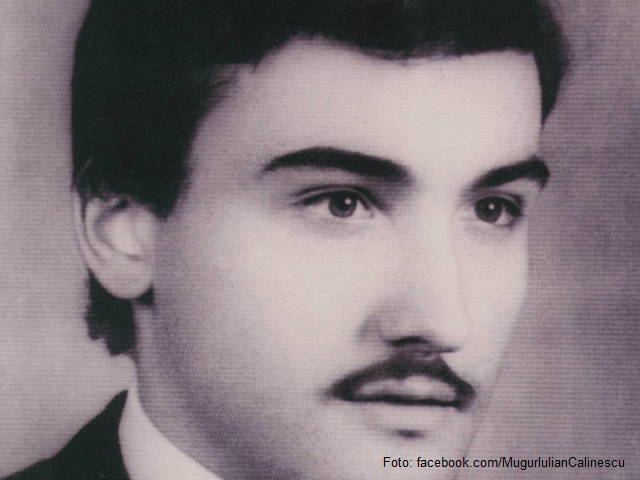

occupying Soviet army at the time. Writer Dan Lucinescu, for example,

was a young army officer. In 2000, he recounted how he was humiliated

by a Soviet non-commissioned officer in the centre of Bucharest:

I was walking

down the street when I ran into a Russian who put a gun to my chest.

Trying to explain that I didn’t understand what he wanted from me,

I somehow realised from his gesticulation that he was angry I hadn’t

saluted him. I told him I was training to be an officer, while he was

a non-commissioned officer, so it should be him saluting me. At gun

point, he ordered me to do a marching walk and to salute him. I

didn’t want a confrontation with him, so I saluted him. He could

have easily shot me.

Dan

Lucinescu’s

unpleasant experience was nothing, however, compared

to what he saw happen a few days later, in broad daylight and in the

middle of Bucharest:

I

saw a teenage girl, probably a high school pupil, walking by. There

were trucks full of Russian soldiers. One of the soldiers suddenly

pulled her, while she started screaming. They took her with them, and

of course no one intervened. They were armed to their teeth.

Colonel

Gheorghe Lăcătușu fought

in the Romanian army alongside the Soviets against the Germans. In

2002, he told Radio Romania’s Oral History Centre how the Soviets

treated everything they laid their hands on:

The

Soviets were seizing everything, trains, vehicles confiscated from

the population, from the German army, from us, the Romanian army. You

had to have a

special dispensation, otherwise

they’d even they your horses if they didn’t have a serial number

somewhere.

They told us they were from the Germans. It was prize of war and we

weren’t entitled to it.

Gendarmerie

colonel Ion Banu recounted in 1995 how a Soviet soldier took his

watch on a street not far from where Radio Romania today has its

headquarters. Close by, he could see the corpse of a Romanian soldier

executed by the Soviets:

When

they returned

from Germany they looked so ridiculous. Each had two or three watches

on their wrists. I even saw a Russian with a watch hanging around his

neck. Once

I

was buying an envelope to write to my parents and

I was wearing a very beautiful watch which I had received as a gift.

A Cossack unit was just passing by, with their big and heavy horses,

and one of them saw my watch and came up to me. He said ‘davai,

davai’, meaning to give him my watch. I was carrying a gun so I

said: ‘It’s mine!’ But he just snatched the watch from me. He

was carrying a machine gun. They wouldn’t hesitate to shoot you. I

saw so many terrible things. On Cobălcescu street, for example, it

still pains me to remember, I saw a Romanian colonel shot dead, his

wife near him. He was lying in

the street, shot by the Russians. They’d do that kind of thing:

they would take a man’s wife, rape her and shoot the husband.

A

teacher fromȘieuț,

in

Bistrița-Năsăud,

Vasile Gotea also

served as an officer in the Romanian army. In 2000, he recounted how

he came close to being shot by the Soviets three times:

I

was almost shot three times. All kinds of disorganised troops that

had passed through the front line were roaming about, through the

villages. Not far from my house, they found what they thought was

wine, but was in fact a recipient with a lid full of grapes to be

kept for winter. They asked me for wine, but there was no wine. I

told them I didn’t have any and they wanted to shoot me. Another

time they took me

behind

the school, put a gun to my chest, asked me to raise my hands and

then

went

through my pockets, taking everything they found and my watch. And

another time, a man was passing by in a cart pulled by an ox and

about 16 Russian women got on the cart, demanding he took them where

they wanted to go. I must have said something and they immediately

pointed their guns at me, ready to shoot. One wrong move and I’d

have been shot. So I didn’t say anything anymore and the cart drove

by.

The

Soviets’ encounter with Romania was violent and left painful

memories and resentment which

won’t be erased from history books

any

time soon.